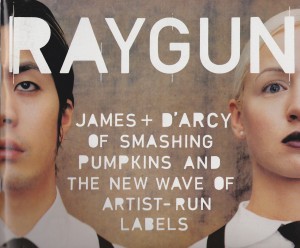

This  was the cover story for Raygun #42 in December, ’96. The magazine got a cover shot that would help sell issues, while James and D’arcy got a chance to promote the label they’d recently formed with Mercury. My cynicism about the venture’s odds of success turned out to be justified, though it brings me no satisfaction to say so. The Fulflej LP D’arcy and James were so excited about didn’t excite the kids quite the way James had anticipated. The band’s Wikipedia page sums up what happened after that thusly: “Their song, ‘Shift Into Turbo’ was featured in Turbo: A Power Rangers Movie, which came out the following year. Fulflej also recorded another album, ‘To Keep A Long Story Long’ in 1998, though it was only released through MP3.com. The band called it quits in 2000.”

was the cover story for Raygun #42 in December, ’96. The magazine got a cover shot that would help sell issues, while James and D’arcy got a chance to promote the label they’d recently formed with Mercury. My cynicism about the venture’s odds of success turned out to be justified, though it brings me no satisfaction to say so. The Fulflej LP D’arcy and James were so excited about didn’t excite the kids quite the way James had anticipated. The band’s Wikipedia page sums up what happened after that thusly: “Their song, ‘Shift Into Turbo’ was featured in Turbo: A Power Rangers Movie, which came out the following year. Fulflej also recorded another album, ‘To Keep A Long Story Long’ in 1998, though it was only released through MP3.com. The band called it quits in 2000.”

Early in 1980, when the Clash came to New York City to play the Palladium, my friend and I joined the majority of the crowd in booing opening act Joe Ely. I did this mostly because I was a fifteen-year-old dunderhead, and hating the opening acts at rock concerts was as much a part of the ritual back then as holding up lighters when our beloved headliners left the stage. Ely’s songs were all pretty slow, and his voice was pretty low, so the crowd eventually got louder than the guy performing. It was painful and embarrassing enough that the members of the Clash felt compelled to come out on stage and dance around in trench coats while Ely sang, just so the crowd would start clapping, which, like good little robots, we did.

Eight years later, someone gave me a Joe Ely tape: Lord of the Highway. My friend and I were touring with our own band now, and knew what it was like to play for a roomful of people who just wanted us to hurry up and finish so whatever group they actually paid to see could take the stage. Experience and maturity had refined our tastes, so we were ready to listen to the tape with open ears.

We decided he still sucked, and tossed the cassette out the window of our van, figuring, if he was the Lord of the Highway, he’d be pleased.

The point of this little prologue is to explain that I get suspicious when famous acts reach the point where they decide it’s not enough that millions of people worship them, now we all have to worship the bands they like, too. So the prospect of artists starting up record companies to inflict their old heroes and new discoveries not just on a captive room full of fans, but on the whole damn world at once, only turns my dread up another notch or two.

It’s like when actors decide what they really want to do is sing. They might actually be pretty good, but nobody gives a fuck. I have a good friend whose band put out an LP for Apple Records in the early ’70s. No, you never heard of them. You know why? BECAUSE THEY WERE ON APPLE RECORDS!

It’s a little too easy to resent musicians who extend their tentacles into the business world: if they’ve been able to amass the requisite levels of cash and clout to start up a bona-fide record company, chances are they’ve done so by reaching that media-saturation point where even fans get irritated when their faces pop up on TV or magazine covers, again. The Smashing Pumpkins certainly qualify there.

Of course, it’s that infuriating bald guy who does most of the writing, singing and talking for the Smashing Pumpkins. And it’s what my editor referred to as “the other two”– guitarist James Iha and bassist D’arcy — who’ve started the label, this time: Scratchie Records. And I have to admit, that’s the best name for a record company I’ve heard in a long time. Anyway, they’ve just signed a deal with Mercury to distribute and market all their releases, which means somebody thinks they’re on to something.

Besides, the Smashing Pumpkins are as proud of their business savvy as they are of their music. To me, they always sounded kind of grand, and I mean that precisely how a pretentious seventh-grade girl might: trying to make something small sound really big. But so what? Several million people obviously disagree.

The Smashing Pumpkins have sold an awful lot of records. I have no idea why, so I ask the Pumpkins if they know what made them huge. D’arcy says, “We believed in the music and we worked our asses off. And we had good business sensibilities. At the time we understood — and wanted, also — that it was important to work our way up slowly, and have a really solid foundation, and fan base. You could almost say, yes, it’s been a kind of plan, we pretty much knew a lot more what we were doing than most people. I think we really had a good sense of what was going on in the music industry with the whole alterna-rock thing, and what was necessary to make it work and stick around for a long time. Mostly it comes down to common sense and hard work. And, I think we write really good music.”

The Smashing Pumpkins have sold an awful lot of records. I have no idea why, so I ask the Pumpkins if they know what made them huge. D’arcy says, “We believed in the music and we worked our asses off. And we had good business sensibilities. At the time we understood — and wanted, also — that it was important to work our way up slowly, and have a really solid foundation, and fan base. You could almost say, yes, it’s been a kind of plan, we pretty much knew a lot more what we were doing than most people. I think we really had a good sense of what was going on in the music industry with the whole alterna-rock thing, and what was necessary to make it work and stick around for a long time. Mostly it comes down to common sense and hard work. And, I think we write really good music.”

You’ll notice that, while her answer begins and ends with music, the emphasis is on all the work that goes into it. And nowhere in her list, ever, does she mention luck.

That makes sense, if you’re in the Smashing Pumpkins. The Pumpkins’ devotion to the actual job of being in a band is undeniable. They were probably one of the first groups that, given a choice, decided to release their record on an independent label not because they wanted credibility, but because it was a good business decision. They are the only band I know of who have taken the term “careerist” as a compliment. It doesn’t mean they don’t have chops; it just means they got them heard.

D’arcy seems convinced the lessons she’s learned as a Pumpkin are all it takes to lead a young band through the obstacle course of the music industry. “You’re just going along blind, you’re this young band, and you don’t know anything. We’ve been through it already. That’s kind of a big part of the reason that we’re doing it, in a way. If we can’t do it . . . it would be pretty pathetic if we can’t make this work.”

But understanding how the business works doesn’t necessarily make you a businessman — just how much do you think economics professors get paid, anyway? Pressed for details about the structure of the company, the terms of their deal with Mercury or the division of labor among the partners, both James and D’arcy lean toward helplessly general answers. D’arcy says, “We help with a lot of the business decisions,” but isn’t too keen on specifying any. When I ask James if there’s a legal document somewhere, detailing who put in what and how the money gets divvied up once the company turns a profit, he says, “It’s all pretty fluid. I think basically we’re all just — Jeremy’s the president.”

To be fair, I don’t get the sense that D’arcy and Iha are unable to give me specifics, just unwilling; they’re very polite, but cautious with their facts. Later, on the phone from Scratchie’s office in Chicago, label president Jeremy Freeman is perfectly happy to tell me the six partners have a legal agreement, dividing the company into specific shares according to each’s contribution. He also explains, patiently and pragmatically, the outlines of Scratchie’s arrangement with Mercury, its potential benefits, and some possible dangers.

To hear these two tell it, though, Scratchie Records sounds more like a wacky sitcom pilot than a business. D’arcy’s brother-in-law Jeremy Freeman and his friend Jamie Stewart had been talking about setting up a label to sell Jamaican 7″ singles in the U.S. D’arcy, her husband Kerry Brown (who plays drums in Catherine) and Iha (who’s D’arcy’s ex-boyfriend) had been thinking about starting up a label of their own. The five decided to join forces, and brought in another musician, Jeremy’s childhood friend Adam Schlesinger. “At the beginning,” says Iha, “we just threw them money. D’arcy put in some money, and Adam put in some money. Jeremy couldn’t pay his rent and his phone bills.”

Can’t you just see them holding a board meeting in a suitably urban coffee shop? Iha and Brown trade put-downs. Meanwhile, Jeremy’s not talking to D’arcy due to some unresolved spat with her sister. Jamie just sits there going, “Guys, we have work to do.” Someone hits the canned laughter button.

Actually, Scratchie has grown quickly and efficiently. Freeman claims he, D’arcy, Brown and Iha first discussed the label in April of ’95, and had it officially running three months and $30,000 later. They released mostly dance and alternative 45’s, plus a compilation LP of dancehall reggae. It’s now just over a year later, they’ve finalized the deal with Mercury, and have a number of releases slated for the coming months. They’ve got bands that have been around, like the Chainsaw Kittens and the Frogs (whose concept EP, Starjob, was produced by another Smashing Pumpkin, Billy Corgan). They’ve got brand new bands, like Schlesinger’s side-project, Fountains of Wayne, and Fulflej. And they’ve got what Iha calls, “the other side of Scratchie,” dance acts Jeremy dug up, like Pancho Kryztal.

Since D’arcy and Iha don’t pretend to know very much about dancehall reggae, I’m not going too, either. But we can talk about the rock bands. We can state with confidence that not only do none of them suck, most of them fall on the happy side of exciting. That’s an amazing feat for any record company. None of them sound anything like the Pumpkins (that would be gauche), but you can hear why a Pumpkin would like them: they’re all fond of their guitars (even influence-blending Fulflej), and they all share a musician’s love of complex arrangements tempered by a businessman’s recognition that ya gotta have singles. Like the Pumpkins, each sounds new in a most familiar way — except for Fountains of Wayne, whose retro tendencies make them sound very familiar, but still leave room for a press flack to say, “There’s something really unique about what they do.” Listen to three or four Scratchie records in a row, and you can be forgiven for thinking James and D’arcy started this whole enterprise just so they could meet some new people to sit around with in hotels talking about obscure ’70s bands.

Right  now, however, they’re sitting around in a hotel room talking about their record company. James is just trying to do his job conscientiously. He’s very aware of the tape deck. When he says someone’s name, he spells it out. He frets that an answer will “read really boring.” And he has a frustrating habit of answering the question he expects rather than the one that’s asked. D’arcy is the True Believer. She talks about every band, especially Fulflej, like their mothers were all killed in a plane crash, and she’s the concerned aunt who’s taking them in.

now, however, they’re sitting around in a hotel room talking about their record company. James is just trying to do his job conscientiously. He’s very aware of the tape deck. When he says someone’s name, he spells it out. He frets that an answer will “read really boring.” And he has a frustrating habit of answering the question he expects rather than the one that’s asked. D’arcy is the True Believer. She talks about every band, especially Fulflej, like their mothers were all killed in a plane crash, and she’s the concerned aunt who’s taking them in.

D’arcy: I dragged James in kicking and screaming once we had–

James: What do you mean!? You called me one day, “There’s this record label . . .”

D’arcy: I forced you to sit in my car for like an hour and made you listen to Fulflej.

James: No, I wouldn’t sit there for an hour.

D’arcy: Yeah, because you wouldn’t stay, you wouldn’t listen. You’re like, (puts on a grumpy voice) “It’s good. The kids’ll buy it.”

Raygun: Did you say that, James?

James: I didn’t understand at first. (to D’arcy) You pissed me off. I only listened to like two and a half songs.

D’arcy: I had to seatbelt him in and lock the doors.

James: You’re over-exaggerating.

D’arcy: Maybe a little. I had him by the ear. I was in the driver’s seat. I’m always in the driver’s seat.

James: She thinks so. Could you stop shaking or whatever you’re doing?

D’arcy: No.

James: So what else do you want to know?

There’s an intriguing line about Fulflej in some Scratchie press release: “D’arcy gets this weird look of excitement every time she hears them and repeats, ‘This is why I got into music in the first place.'” I read that sentence over and over when I first saw it, because, for all its enthusiasm, it’s also got a sad ring to it, as if jumping up and down at Madison Square Garden just wasn’t doing it for her anymore. Maybe the whole record company thing is just a way of re-connecting to a musical enthusiasm that the business of being a pop-star beat out of her.

It’s a nice theory, but I’m about to learn it doesn’t fly.

Raygun: While we’re on the subject of Fulflej . . .

James: They’re a dynamic new band of the nineties, combining hip hop sensibilities, atop epic dramas, with rather fantasy-like lyrics and complex musical arrangements.

Raygun: And the kids will buy it.

James: Kids will love it.

D’arcy: You said, “The kids will buy it.”

James: I thought I said the kids will love it.

D’arcy: Now you said that.

James: I don’t remember.

D’arcy: No, you didn’t, you said, “It’ll sell records. And the kids will like it.” That’s what you said.

Raygun: There’s a quote from D’arcy in some press release (I dig the relevant quotation out of my notes). When I first read it, it sounded exciting, like the last thing a record mogul would ever say. At the same time, there’s something kind of forlorn about it. You’re in the Smashing Pumpkins, but here you are saying this is why I got into music.

James: Yeah? So?

D’arcy: What do you mean?

James: What’s your point?

Raygun: We’re getting to the question that comes after “What is Scratchie?” Which is, “Why are you doing this?” We can assume you’re rich enough that it’s not a business investment.

D’arcy: Yeah?

Raygun: So why get involved with a record company? Do you think you can do it better than everybody else?

James: I don’t think it’s necessarily that we can do it better–

D’arcy: I think we can. I think we can.

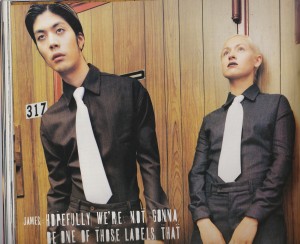

James: I think there are a lot of labels that have done well by bands. And there are a lot of labels that screw bands. Hopefully we’re not gonna be one of those labels that screws our bands.

D’arcy: “Hopefully,” James says. What are you, planning some strange transformation into the Evil James?

James: Well, if every record we put out bombs. . .

D’arcy: He’ll do whatever it takes!

James: You’re really pissing me off.

D’arcy: I guess I’m just a romantic. James, he’s one of those number-cruncher guys.

James: I’m just speaking realistically. I don’t think the record business is like this teen fantasy. I don’t expect all of our bands to sell a million records, but I don’t want them to sell 100 records just to their friends. I don’t sit and think about how many records a band’s gonna sell, but I try to get involved with as many little things as I can with the bands, because I know that the overall picture will help this band someway or another, some number way. Either they get more people to their shows, or enough people will be interested if they read our promotion to actually go out and buy the record or see them.

D’arcy: I think we could play the game as good as anybody, without having to kill people, walk over people, while we’re doing it.

D’arcy discusses the bands on her label the same way she explained the Smashing Pumpkins’ success: she talks about what she wants for them, but she doesn’t concentrate on their music. Not because she doesn’t care, but because it’s beside the point. She wouldn’t have signed them if she didn’t like them, now her job is getting them heard. And she’s utterly convinced that’s just a matter of following the right steps, in the right order. “We were basically looking just strictly for distribution for a long time. But most of the labels were of the mind-frame, well, what are we gonna get out of this? Even if we had the money, we still wouldn’t have the muscle to get the records out. That’s what’s really important to us. If people know about it, and hear it, they’ll like it. So, that was how we ended up where we are with Mercury. Just give and take kind of thing.”

You’ve heard that before, haven’t you? It’s the sound of every indie-band explaining why they’re going with a major, now. It’s the same reasoning the radical bomb-thrower on your campus ends up joining the Democratic National Committee, so he can “change things from the inside.” Except it’s not annoying coming from D’arcy, because she never claimed she was throwing bombs in the first place. She thinks the music business works fine just the way it is. She only wishes everyone could be nicer to the bands.

heard that before, haven’t you? It’s the sound of every indie-band explaining why they’re going with a major, now. It’s the same reasoning the radical bomb-thrower on your campus ends up joining the Democratic National Committee, so he can “change things from the inside.” Except it’s not annoying coming from D’arcy, because she never claimed she was throwing bombs in the first place. She thinks the music business works fine just the way it is. She only wishes everyone could be nicer to the bands.

Fulflej seem closest to her heart. “I want them to be huge. HUGE! Fulflej is like a little science experiment for me, though. All the bands that I know, everybody has paid their dues, you know, and by the time, IF you ever get any success, by the time you get it, you’re really fucking cynical and jaded. And it would be interesting, I think, to be able to get a band to be huge without them being scarred for life along the way. And see what happens. See how it turns out. See if they change. It would be really interesting — they’re the nicest, sweetest, most innocent guys.”

“Well, and their music is good,” James says.

But D’arcy doesn’t think that even needs to be said. “Yeah. I mean, obviously. To me, anyway.”

Raygun: Back to why you started a record company. You mentioned helping bands without stepping on people. The Smashing Pumpkins, from where I’m sitting, anyway, certainly seem well-served by the music business. So what specific pitfalls are you talking about?

D’arcy: I think that there are a lot of artistic things that the record companies try and get involved with where bands are concerned that they shouldn’t try to be involved in. It could be anything from which songs make it on to the album to what you wear, you know, your image. And artwork, videos, etcetera, etcetera.

Raygun: You always hear that, but whenever I talk to a band, they always say, “No, no, the company’s been really good to us.”

D’arcy: No, it’s happened to us. Always, the record company is trying in some way to influence us. We have made a lot of compromises. Because they’ll say, “We think this should be the first single. You can do whatever you want, but . . .” That’s usually the way it works.

James: That happened to this band we know, but we won’t mention them.

Raygun: OK, so now you’re on the other side. What’s the weakest song on the Fulflej record?

James: Well, there’s one song that’s nine minutes long. I wouldn’t say it’s the weakest artistically. But commercially speaking, if they wanted to put that out, I would say, “Well, it’s not a very smart move, cause no one’s ever gonna play a nine minute song unless it’s ‘Hey Jude.'”

D’arcy: We’d try and give ’em advice, but in the end, if that’s what they want to do, then, you know, we’ll try and help them along the way.

James: Well, in this case, I don’t think Mercury would support putting out a nine minute song. It would just be like going upstream, making a really bad business decision.

D’arcy: Well, I don’t want them to be involved, so much, in that manner. I don’t know, they seemed to understand that, at the meeting, but, who knows.

Raygun: Honestly, if you were to give them a nine minute single, exactly what you were just describing would happen. They’d say, “You can do whatever you want, but . . . ”

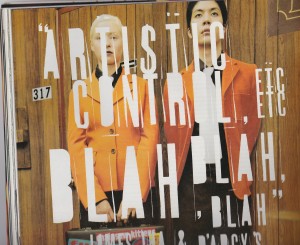

D’arcy: I don’t know. We did the best that we could. We went into the meetings with them, and we explained to them that we wanted to, you know, be the ones dealing directly pretty much with the bands, and for the bands to have their artistic control, etcetera, etcetera, blah, blah, blah. And they always said, “yes, yes, yes,” at the time. But we’ll see.

James: I think the difference is, the band we were talking about before, they were talking about two different singles, and they were both basically pop singles, three minutes long.

Raygun: It doesn’t seem that heinous to me for a record company to say, “This is the song we want to push.”

James: It’s hard to explain it without saying the band name.

D’arcy: If it’s something absurd, if the band wants to do something totally self-destructive, that’s one thing. But if it’s like, we think the cover of this single should be blue, oh no we think it should be red — that’s absurd, you know? There are times when decisions like that, it gets put off and put off and put off until the last minute, then there’s no way to do it except the record company’s way. It’s like they do it on purpose.

Raygun: So give me some specific examples from your own career when you’ve felt hampered by the record company.

D’arcy: No, I don’t think I want to go there.

James: We can’t really–

D’arcy: We can’t do that.

James: We can’t really say. Well, like, one thing. When we first went to Canada, we got like no support, like on our Caroline release. It was a pretty big indie record in America, 350,000 records. And we go to Canada, hopefully to play a small club, or a big bar, and there’d be ten people. No support, nobody really going to radio, nobody stepping up to bat for us. And now, on this record, we’ve sold ten times platinum, in Canada. Why didn’t anybody think of it back then? “This band could be huge.” They just didn’t do it. Some territories, they’ve never even put out our records until this one.

D’arcy: They send you to tour in places, where it’s like, where there’s been no preparation, no promotion, there’s no records even there.

James: It’s those sort of pitfalls that we want to avoid.

Raygun: So those are more business things than artistic.

D’arcy: I think we kind of got off the subject. I don’t even remember the original question, anymore.

Raygun: You said you felt you had to make compromises.

D’arcy: It’s like what I was telling you, with the artwork. You’ll say I want it blue and they’ll send it back a different color. “Oh, we misunderstood you.” How can you misunderstand blue? Finally, the deadline comes, and it’s blue, or whatever color that they wanted, because it’s too late to do anything about it.

Raygun: But your soul’s not invested in whether it’s red or blue.

D’arcy: I’m just giving you a very general example of how the band will get fucked. With stupid things. Just stupid little things.

James: We’ve never been messed with majorly, as far as artistic direction, so I can’t give a first hand example of the Pumpkins being told in the studio, “You can’t record this.” But I’m sure there’re bands that have.

Raygun: I’m looking for specific pitfalls you’ve encountered that you’re trying to help the guys on your label avoid.

James: Well, you know.

D’arcy: OK, for instance, if a label doesn’t even like the record, they could just say, no, write a new one, this sucks. And I know that that has been done before. You want me to name names and be specific. I don’t wanna do that. They’ll send A&R people into the studio while you’re recording, put the pressure on. Sit there and argue with you about singles, what should or shouldn’t be on the record.

Raygun: None of these sound too soul-damaging, you know?

D’arcy: On a constant level, day-to-day thing, it’s very irritating. And if you work so long and so hard on something, I mean, I don’t know if you can understand that, and to have somebody come along and say, “It’s crap.” That’s pretty damaging.

James: The good thing about most of us being musicians is that we can explain to them the business side of why things are happening, and also tell them, from a musician’s point, this is why it’s being done, too. This is the end result of some decision that we made. Touring, recording, whatever. They can take it or leave it. I think at least they get a sense that we’re trying to do right by them, or explaining things as best we could, you know, from both sides of the coin. I think that’s a big plus about Scratchie, being much more understanding.

D’arcy: And we can be there to fight for the band, if that machine does kick in, and know where they’re coming from, and try to see the other side. When you’re a young band like that, a lot of times you think that you can’t say no. And there definitely have been instances when we couldn’t, but there are many, many instances where you can, and you can fight for your cause, and make them understand, but lots of times the record label will be like, “Well, we think you should do this,” and you’re just like, well, if you say so . . .

That’s all true. The bands on Scratchie are lucky to be working with artists, rather than accountants: Scratchie’s partners can stretch their bands’ recording budgets by functioning as in-house producers, and they’re less likely than your average bean counter to cavalierly insist on needless expenses which end up getting charged back to the groups. James even lent the Fulflej guys money when they were dead broke. But it’s sort of exasperating that the artists have decided to play by the accountants’ rules. I hear a trace of defeat when D’arcy uses phrases like, “we did the best we could;” “it’s a give and take kind of thing;” and, “artistic control, etcetera etcetera, blah, blah, blah.” There’s a whole set of assumptions the music industry rests on that D’arcy never bothers to question, and there’s an inherent hubris in the way she and James equate minor indignities with artistic compromise, especially since one of the major benefits they think they can offer new bands is the very type of advice they bristle at when record companies give it to them.

D’arcy’s the true believer, but what she believes in, mostly, is that the music business makes sense. It’s hard to argue with her — she’s like a kid who writes a melodramatic short story and insists the teacher can’t give her a bad grade, because it really happened. There is another, simpler view of the music business, which, if I were engaged in an academic debate, I would phrase this way: NOBODY HAS A FUCKING CLUE WHAT THEY’RE DOING! According to this view, the Smashing Pumpkins’ phenomenal success and Scratchie Records’ quick partnership with Mercury aren’t exceptions, they’re proof.

The music business operates on the principle that nobody knows what kids want to hear. Labels release far more records than they can effectively market, hoping one or two click. I have a friend who plays pool this way: he just shuts his eyes and whacks the cue ball, figuring something’s got to make it into a hole. He wins more often than you’d think. The Smashing Pumpkins clicked. In a very real sense, D’arcy and James have already helped a number of young bands: a lot of the money their record company made off of them was funneled into signing and releasing new acts.

A lot of those acts, however, don’t click. Their CD’s just sit in the racks at Tower. James and D’arcy don’t think that’s an inevitable result of the confusion that drives the industry. They think it’s the sorry fate of bands who don’t know how to play the game. In the Pumpkins’ ordered universe, the music business is like a big dinner party, and they want a chance to do the seating chart.

Raygun: What’s going to be your definition of success?

James: It’s sort of like a two-tiered system. We’re not expecting Phoenix Thunderstone to sell half a million records.

D’arcy: But I’d like to be able to help them to be able to at least make a living at what they want to do, which is music, and not have day jobs. It can be done at that level.

James: I think it just depends on the band. An ambient trance record isn’t gonna sell 300,000 records, either. But a band like Fulflej could sell that many records.

Raygun: Does Mercury automatically take on any band you sign?

James: No.

D’arcy: Oh, no, no. They’ve taken a special interest in Fulflej, Chainsaw Kittens.

James: The first Frogs EP will probably go through their independent distribution. Your average punk rock, mom and pop stores. But with the Frogs’ LP, that will probably go through Mercury proper. But for right now, Phoenix Thunderstone will go through this independent system, too.

D’arcy: It would be pointless for Phoenix Thunderstone to be with Mercury. It would be absurd.

James: That’s not to say their next album won’t. We just want to start ’em at this level right now. And the bands all know that, too.

Raygun: What does “take a special interest” in Fulflej mean?

James: They like them. They think they’re gonna sell records.

D’arcy: They thought that they were ready to try and take it to a higher level. Like they have enough strong material, I think they’ve been playing enough shows. To me it’s just a growth process. Like with our band, we stayed with Caroline purposely, we could have gone to a major label, but we just didn’t think we were ready, like, mentally. I mean, maybe the music was there, but we didn’t feel like the fan base was there, we didn’t feel like we were personally ready for it. Mercury understands that Fulflej — they’re not just gonna throw it out and it’s gonna be huge instantly. They’re willing to work with it, and nurture it.

James: It’s still gonna be like a very independent feel.

Maybe there’s a record company executive somewhere who finalized a deal with some hotshot kids with guitars by shaking their hands and saying, “Guys, your music confuses me. I have no idea if anybody’s gonna buy it. We’ll give your album six weeks. If it’s not making some noise, you’re all fired.” But I kind of doubt it.

That doesn’t mean the folks at Mercury are lying. It just means there’s a better-than-average chance they’ll get distracted by some act that doesn’t need quite so much nurturing. James and D’arcy’s conviction that they can keep Mercury focused on their bands might be misplaced, but it’s also refreshing. I wish them well. I hope they’re right. I hope they can make lightning strike twice.