I  had been looking for an excuse to spend some time at a monastery for a while, so was very glad when Raygun accepted my pitch to write an article about the experience in 1994. Not sure why I wasn’t willing to go just for the sake of going. But monks who bred and trained puppies to support themselves seemed like people I just had to meet.

had been looking for an excuse to spend some time at a monastery for a while, so was very glad when Raygun accepted my pitch to write an article about the experience in 1994. Not sure why I wasn’t willing to go just for the sake of going. But monks who bred and trained puppies to support themselves seemed like people I just had to meet.

In 1970, high atop a rocky hill in upstate New York, three miles east of the small town of Cambridge, a group of monks built a small wooden church topped with gold, onion-shaped cupolas. It looks a little bit like the Kremlin might if the Kremlin were much tinier and made out of Lincoln Logs. This is New Skete. The monks still live and worship on this hilltop today.

What am I doing here? This is a question I have been asking myself since before I even arrived.

I asked it in my rental car, speeding up route 22 on an achingly beautiful October afternoon. I asked it in the bar in Hoosic Falls, where I stopped for my last beer for the next four days. I asked it in the bar in Cambridge, where I stopped for my other last beer. I asked it as, following the instructions Brother James had given me over the phone, I drove up New Skete Road, parked in front of the guest house, and walked around to the gift shop.

The gift shop was empty; a sign beside a hand-held bell said, “Ring for brother on duty.” I did. A bearded man wearing a beret and a butcher’s apron appeared from the back. He introduced himself as Brother Ramon. Brother Ramon told me to go inside the guest house and look for a door with my name on it. He told me to walk up the hill to the dining hall at 5:15 for dinner. That gave me another hour and a half to sit in my little room and ask myself what I was doing here some more.

So when Brother James, the guestmaster, sits me down before dinner and asks me that very question, you would think I’d have my answer all prepared. I mention the crowded, noisy conditions of the city where I live, emphasizing how much I hate being woken up by sirens at four a.m. When Brother James says nothing to this, staring at me as though there must be more, I mumble something about reaching a crossroads in my career, then something else about my wife’s pregnancy and my own nervousness.

All these things are true. More importantly, all these things sound much, much better than what I have come to realize is probably the truer answer: Kira went to a monastery in a recent episode of Deep Space Nine, and it looked like fun.

Why I chose this particular monastery is easier to explain. The monks of New Skete love dogs. They support themselves by breeding and training German Shepherds. Every brother has his own dog; some have two or more. The dogs sleep in the monks rooms, and follow them everywhere except into church.

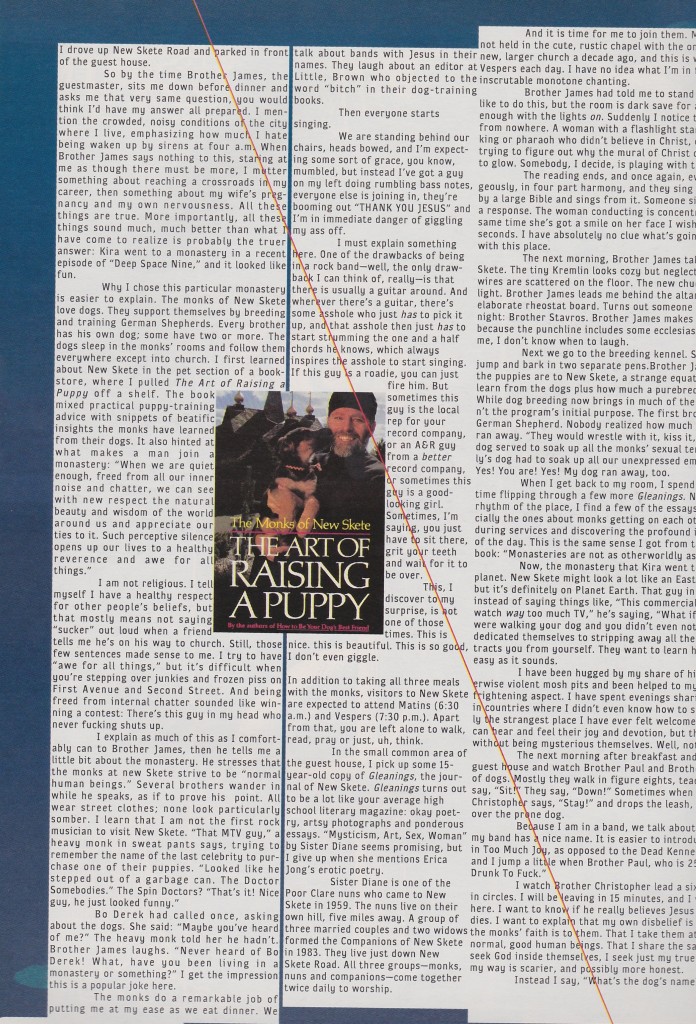

I first learned about New Skete in the pet section of a bookstore when I pulled The Art of Raising a Puppy off a shelf. The cover said, “By the authors of How to be Your Dog’s Best Friend.” The authors were listed as The Monks of New Skete. The cover also had a picture of a monk in a black robe and cap holding up a German Shepherd puppy. The puppy was licking the monk’s face.

The inside of the book was just as intriguing. It mixed practical puppy training advice with snippets of holy wisdom the monks have learned from their dogs. It also hinted at what makes a man join a monastery: “When we are quiet enough, freed from all our inner noise and chatter, we can see with new respect the natural beauty and wisdom of the world around us and appreciate our ties to it. Such perceptive silence opens up our lives to healthy reverence and awe for all things.”

I am not religious. I don’t presume to know everything, but I don’t believe in God. I tell myself I have a healthy respect for other people’s beliefs, but that mostly means not saying “sucker” out loud when a friend tells me he’s on his way to church. Still, those few sentences in the introduction made sense to me. I try to have “awe for all things,” but it’s difficult when you’re stepping over junkies and frozen piss on First Avenue and Second Street. And being freed from my internal chatter sounded like winning a contest: there’s this guy in my head who just never fucking shuts up.

I explain as much of this as I comfortably can to Brother James. I tell him I’m in a rock band when he asks what I do. Too Much Joy, I have learned, is a good band name. When checking into Bible Belt motels, you can pass yourself off as a Christian Rock group. I now learn it is equally useful when introducing yourself to a monk. What if we were the Dead Kennedys?

Brother James tells me a little bit about the monastery. He stresses that the monks at New Skete strive to be “normal human beings.” Several brothers wander in while he speaks, as if to prove his point. They all wear street clothes; none of them seem particularly somber. I learn that I am not the first rock star to visit New Skete. “That MTV guy,” a heavy monk in sweat pants says, trying to remember the name of the last celebrity who purchased one of their puppies. “Looked like he stepped out of a garbage can. The Doctor somebodies.” The Spin Doctors? “That’s it! Nice guy, he just looked funny.”

Bo Derek called once, asking about dogs. She said, “Maybe you’ve heard of me?” The heavy monk told her he hadn’t. Brother James laughs. “Never heard of Bo Derek! What, have you been living in a monastery or something?” I get the impression this is a popular joke, here.

The monks do a remarkable job of putting me at my ease as we eat dinner. We talk about bands with Jesus in their name. They laugh about an editor at Little, Brown who objected to the word “bitch” in their dog-training books. They quote from My Cousin Vinny (“Two yutes. Two yutes”). Since it is two weeks before election day, I ask if monks vote. They do. Living on a mountain, they need a good roads commissioner. By the time we have finished all our food, I am beginning to understand what Brother James meant about monks being normal human beings. I’m still pretty self-conscious, but this is more comfortable than dinner with your relatives, say. Then everyone starts singing.

We are standing behind our chairs, heads bowed. I was expecting some sort of grace, but, you know, mumbled. Instead I’ve got a guy on my left doing rumbling bass notes, everyone else is joining in, they’re booming out “THANK YOU JESUS,” and I’m in immediate danger of giggling my ass off.

I must explain something here. One of the drawbacks to being in a rock band — well, the only drawback I can really think of — is that there is usually a guitar somewhere nearby. And wherever there’s a guitar there’s some asshole who just has to pick it up, and that asshole then just has to start strumming the one and a half chords he knows, which always inspires the asshole to start singing. If this guy is a roadie, you can just fire him. But sometimes this guy is the local rep for your record company, or an A&R guy from a better record company, or sometimes this guy is a good-looking girl. Sometimes, I’m saying, you just have to sit there, grit your teeth and wait for it to be over.

This, I discover to my surprise, is not one of those times. This is nice. This is beautiful. This is so good, I don’t even giggle.

I return to my room around 6:15. In addition to taking all three meals with the monks, visitors to New Skete are expected to attend Matins (7 am) and Vespers (7:30 pm). Apart from that, you are left alone to walk, read, pray or just, uh, think.

There are two rooms beside my own in the guest house; both have names on the doors, although Brother James told me one woman who was expected called to say she was sick and couldn’t make it. Yeah, well, I considered the same ploy several times on my way up here. The guest house also has a common area with a small couch and chairs, plus two shelves of books. I glance at some titles: On the Holy Spirit, by St. Basil the Great; Orthodox Synthesis. I settle instead for some fifteen-year-old copies of “Gleanings,” the journal of New Skete.

“Gleanings” turns out to be a lot like your average high school’s literary magazine: OK poetry, artsy photographs and ponderous essays. Just like high school, everything seems to be written by the same three or four people. “Mysticism, Art, Sex, Woman,” by Sister Diane seems promising, but I give up when she mentions Erica Jong’s erotic poetry. Like I said, this is from the 70’s.

The journals, along with some brochures in my room, do help me put together some of the history of New Skete, though. The monks began in 1966, twelve young men straight from the seminary, led by Father Laurence. After two false starts finding living quarters and means of supporting themselves as a community, they settled here, on Two-Top mountain. Because the rocky terrain won’t support farming, they gradually turned to the breeding of German Shepherd Dogs. Their experience raising these led them to the boarding and training of all dogs. They also sell smoked meats and cheeses, and various religious goods.

They were joined in 1969 by a group of Poor Clare nuns, who live on their own hill, five miles away. Hello Sister Diane. A group of three married couples and two widows formed the Companions of New Skete in 1983. They live just down New Skete Road. All three groups, monks, nuns and companions, come together daily to worship.

And it’s time for me to join them. I trudge up the hill toward the church. Most services at New Skete are not held in the cute, rustic chapel with the onion domes. The monks built a new, larger church in 1983 to accommodate the crowds they were attracting, and this is where they conduct Matins and Vespers each day. Vespers is one of those words I’ve heard without ever learning just what the hell it means. I have no idea what I’m in for. I have vague notions of inscrutable, monotone chanting.

A small stream of people flows toward the big church. I follow them inside. One by one they stop in front of an icon, cross themselves, and kneel. I start freaking out. Am I supposed to do this? When it’s my turn, I do some version of a cross (everyone else did it so fast I couldn’t tell if you go left-right or right-left) and just give up.

Brother James has told me to stand in the back and watch. I would like to do this, but the room is dark save for a few candles. Church is scary enough with the lights on. As my eyes adjust I make out several of the monks — in robes, now — sitting in chairs arranged around the sides. I stand in front of a chair in what I hope is the back. More monks and nuns shuffle out of a room beside me. They all head to chairs and sit. Soon I can see clearly enough to realize I’m the only one standing. I sit down.

Suddenly I notice the altar. A light is shining on it out of nowhere. A woman with a flashlight starts reading some text while a monk walks around lighting candles. The woman is telling the story of an old king or pharaoh who either didn’t believe in Christ or did — I lose track because I’m trying to figure out if the newly lit candles can account for the way lights are beginning to shine on the mural of Christ on the opposite wall. Somebody, I decide, is playing with the dimmer.

The reading ends; everyone stands. And once again, everyone starts singing. They sing beautifully, in four part harmony, and they sing everything. When one woman stands alone by a large Bible, she doesn’t read from it, she sings from it. Someone sings a question, everyone sings a response. Some of the words I recognize (“give us this day our daily bread”), most I don’t.

I can’t decide where to look: down, and I keep seeing monk sandals poking out from beneath their robes; straight ahead, and I’m afraid I’ll distract the woman conducting. I try closing my eyes, but then I feel like I’m in Whoville, and all the Who’s are singing Fah-Hoo-Doh-Ray.

Still,  I am falling in love with this place. I have absolutely no clue what’s going on, but somehow everything that happens makes sense. We all came to church in the dark; gradually, as everybody sang, it got brighter. The woman conducting is concentrating very hard, but at the same time she’s got a smile on her face I wish I could borrow for just a few seconds.

I am falling in love with this place. I have absolutely no clue what’s going on, but somehow everything that happens makes sense. We all came to church in the dark; gradually, as everybody sang, it got brighter. The woman conducting is concentrating very hard, but at the same time she’s got a smile on her face I wish I could borrow for just a few seconds.

I was prepared for any sort of weirdness, but I wasn’t prepared to like it. I have spent my life actively despising mindless ritual. Remember, these people attend basically this same service every night of their lives, and another one much like it every single morning. So how come nobody looks like he’s just going through the motions? Brother James glides over to me when the service ends and bids me goodnight. I walk back down to the guest house, wondering if this music is ever going to leave my head.

It’s 8:28, and I’m alone in a spooky room. Somewhere in the dark, dogs and monks are preparing for bed. What the fuck do I do now? I’m a little bit bothered that church made sense. Am I getting old and goofy? I take God’s name in vain a couple of times. Just testing.

I wake up at 6:10 the next morning. Back up the hill for Matins. It isn’t any lighter than when I went to Vespers. The morning service seems as direct and inspiring as last night’s. But my mind wanders a little. The monks and nuns sniffle between songs. Flu season is just beginning. My legs hurt. I’m hungry. I wonder what the dogs make of all this. Last night one line stuck in my mind. The woman at the Bible sang it, alone: “I was a child of happy disposition.” This morning it’s something everyone sings: “Sweeter they are than honey, than dripping honeycomb.”

Breakfast is casual. Monks and companions straggle into the kitchen one at a time, pour some cereal or tell the brother in the kitchen how they want their eggs, and wander off. They all seem just as fogged as the average office staff on a Monday morning. Everybody’s nice to me, but they make fun of one another.

Brother James takes me on a short tour of New Skete. The tiny Kremlin looks cozy but neglected on the inside. Pipes and wires are scattered on the floor. While everybody performs Matins and Vespers together in the large church, one brother a day comes here to keep the other canonical hours, because the monks are so busy supporting themselves with the dogs and the smoked meats (Brother James, whose abstract art has started to earn the monastery nearly as much as a couple of those puppies, gets to spend his days painting).

The new church is less frightening in the daytime. Brother James leads me behind the altar and shows me the surprisingly elaborate rheostat board. Turns out someone was working the dimmer last night: Brother Stavros. James makes a Wizard of Oz joke, but because the punch line includes some ecclesiastical reference that’s beyond me, I don’t know when to laugh.

Brother James explains the reasoning behind New Skete’s approach to the divine services. The monks are members of the Orthodox Church in America, but it turns out most of the church hierarchy consider them radicals, partly because of the way they conduct their liturgies. They sing in contemporary English. They write their own melodies. The joke is that the monks at New Skete have spent more than twenty years studying Orthodox theology and practice. I may be simplifying the point of Brother James’ lecture, but the monks of New Skete conduct divine services the way they do because they have struggled to learn the intentions behind Orthodox Church traditions. They’re not just some crazy kids.

All I know is that I have been to church as much in the last twelve hours as I have in the last twelve years. If you count weddings and funerals. If you don’t count weddings and funerals, I have never been to church. And I understood what was going on anyhow. Brother James nods happily when I say that; there is an historical and scholarly underpinning to the service, but it’s supposed to just make sense on its own. The monks’ worship “isn’t mystery — it’s real.”

The tour takes us to the breeding kennel. Six German Shepherd puppies jump and bark in two separate pens. This is the first I have seen of any dogs. Brother James tells me how important the puppies are to New Skete, a strange equation of how much the monks learn from the dogs plus how much a purebred German Shepherd sells for. While dog-breeding now brings in much of the monastery’s income, that wasn’t the program’s initial purpose. The first brothers apparently had a German Shepherd. Nobody realized how much they needed the dog until it ran away. “They would wrestle with it; kiss it,” James says. I can’t help wondering if that dog served to soak up all the monks’ sexual tension the same way my family’s dog had to soak up all our unexpressed emotions — Whoseagoodboythen? Yes! You are! Yes! My dog used to run away, too.

The kennel, James says, is normally off limits to visitors. I figure this is a natural lead-in to, “and we don’t usually do this, but since you discussed the liturgy so intelligently, I think you can play with them for the rest of the day.” Unfortunately, I realize he just means “so you can’t come up here anymore, OK?”

During this tour, I have slowly realized that Brother James assumes I have come here to solve a specific personal crisis. His talk mostly concerns the philosophy and workings of New Skete, but every once in a while some anecdote about the construction of the chapel or those loveable dogs ends with a moral, which is almost always, “People are afraid of what they don’t know, but you learn by doing.” I think he thinks I don’t want my kid.

I fall asleep when I get back to my room, then wake up feeling guilty that I have wasted some contemplation time. I flip through another couple of “Gleanings.” Now that I’m getting into the rhythm of this place, I find some of the essays a bit more illuminating. Scattered among scholarly analyses of Orthodox practice are simple stories about discovering the profound in the most mundane aspects of the day. This is the same sense I got from the very first page of the dog book: “Monasteries are not as otherworldy as you might imagine.”

Now, the monastery Kira went to was on an entirely different planet. New Skete might look a lot like Eastern Europe’s idea of sleepaway camp, but it is definitely on Planet Earth. That guy in my head hasn’t shut up, but instead of saying things like,”This commercial sucks,” and “You know, you watch way too much TV,” he’s saying, “What if your life changed when you were walking your dog and you didn’t even notice?”

The monks have simply dedicated themselves to stripping away all the everyday bullshit that distracts you from yourself. They want to learn how to be human. It isn’t as easy as it sounds. Personally, I’m distracted by that big mural of Jesus. But maybe its necessary to keep everyone on this mountain from turning into selfish, arrogant hippies, to give all this solitude and contemplation a concrete ideal to work toward (or for), to keep them humble. They come together twice a day and sing to God; by beginning and ending their days that way they create a context for everything that occurs in between. You can hear and feel their joy and devotion. They let you taste the mystery without being mysterious themselves. Well, not too.

At dinner I meet a new guest, Mark. Mark has come up from a seminary in Crestwood to study the monks’ service. He asks me if I’m Orthodox. When I say no, he asks, “What are you?” I say, “Nothing,” then, since that comes out wrong, change my answer to curious.

Mark has heard a lot about New Skete, not all of it, one senses, complimentary. Brother Paul, the youngest and maybe the friendliest monk, goes on a mini rant about how the Orthodox hierarchy assumes New Skete rejects tradition, even though their stated goal is to rediscover the original purpose of Orthodox practices. Later that night, I hear Father Laurence giving Mark pretty much the exact same speech.

Tonight’s Vespers soundbite is, “Bless those who travel by land or sea or air or space.” It’s pretty funny, when you sing it.

After Matins and Vespers the next morning, I sit outside the guest house and watch Brother Paul and Brother Christopher train a series of dogs. Mostly they just do heel, sit and stay, but every so often Brother Christopher has one of the dogs lie down while he jumps back and forth over its body.

Because I am in a band, we talk about music. I confess I was glad my band had a nice name when I first got here, as opposed to the Dead Kennedys. Both Brother Christopher and I jump a little when Brother Paul excitedly remembers “Too Drunk to Fuck.” Turns out we were both at the same R.E.M. concert, once.

I want to ask the two monks what drove them here. I want to know if they really believe Jesus is waiting for them when they die. I want to explain that my own disbelief is just as comforting to me as their faith is to them. That I take them at their word they want to be normal, good human beings. That I share the same desire, but where they seek God inside themselves I seek just my true self, hoping its good. That my way is scarier, and perhaps more honest.

Instead I look at Brother Christoper, walking a German Shepherd in circles, and say, “What’s the dog’s name?”