This  one was presented at the 2011 Pop Conference. David Lowery, who also presented that year, suggested that reluctance to license music to commercials was mostly about class, as you have to be pretty privileged in the first place to turn down money. That didn’t make me feel much better, but another thing he told me sure did: he’d spent time as a quant for some investment firm, and he said the traders there had a very unique take on being an unrecouped band. “That means you won!” they told him, when he explained how major label contracts tended to work. The way they looked at it, being unrecouped was less a mark of failure than of getting the better end of a transaction.

one was presented at the 2011 Pop Conference. David Lowery, who also presented that year, suggested that reluctance to license music to commercials was mostly about class, as you have to be pretty privileged in the first place to turn down money. That didn’t make me feel much better, but another thing he told me sure did: he’d spent time as a quant for some investment firm, and he said the traders there had a very unique take on being an unrecouped band. “That means you won!” they told him, when he explained how major label contracts tended to work. The way they looked at it, being unrecouped was less a mark of failure than of getting the better end of a transaction.

The closest my band, Too Much Joy, ever came to breaking up was in 1991, as we argued about whether we should accept a lucrative offer to record a radio jingle for Budweiser, which I personally considered the second worst beer in America.

The argument began in our manager’s office. My position was not nuanced: commercials were antithetical to every reason we’d formed our rock band in the first place. This was debased, and rock bands – especially indie rock bands — needed to be pure.

My bandmates were unswayed. They pointed to the fact that we would be paid a large advance, which we sorely needed. They emphasized that Budweiser would not be using our own music, simply hiring us to play their theme song. They repeated the dollar amount of that advance.

The debate continued for weeks. Because I was even more stubborn in my youth than I am today, it was still going on after I had been outvoted 3 to 1 by the rest of the band, and we were recording the jingle in a fancy Manhattan studio.

Though I had been outvoted by my more mercenary band-mates, they were kind enough or just suspicious enough of their own motives to accommodate what remained of my punk rock principles. I was the lead singer, but they introduced me to the spot’s producer as the tone-deaf rhythm guitarist, the idea being that perhaps we could record the tune without any participation from me.

We first met the producer at his Manhattan apartment. Lloyd was probably a very nice and accomplished musician, but he looks like this in my memory:

and I couldn’t help but hate him as he sat behind a Casio keyboard and walked us through the changes to Budweiser’s jingle.

Although the tune sounded like it had been written on that very same keyboard, Anheuser-Busch’s agency had recently taken to having indie bands record it in their own style. In fact, the agency had provided a surprisingly lengthy list of bands with way more cred than TMJ who’d taken the same deal, and said list had figured prominently in my bandmates’ efforts to win me over to their way of thinking.

Happily, Lloyd fell for our ploy, though he did keep asking Jay, the guitar player who was posing as me, to “do that gruff thing you do on the record.” Watching Lloyd frown while searching for encouraging ways to say, “No, that’s not quite it,” every time Jay tried and failed to imitate me went some way toward re-bonding the band members.

They also refused Lloyd’s cautious but repeated efforts to get us to sing the words of the jingle to the music from a song of ours called “Long Haired Guys From England” that was currently doing OK on college radio. Though I remained pissed at the band, it was nice to know they still drew the line somewhere.

In the studio, Lloyd continued his doomed efforts to get Jay to “do that gruff thing,” playing a bit from “Long Haired” where I growled a verse, and lamenting, “It just doesn’t sound the same,” whenever Jay tried to recreate the timbre. We pretended the sound had been the ingenious result of some expensive studio effect employed by our L.A. super-producer, and insisted we were having the same problem live. Jay, bless him, also strapped on my telecaster when Lloyd said it was time to lay down the rhythm guitar parts. “I’m better than he is,” Jay said, “so I play all the parts when we record.” That much, at least, was actually true.

It looked like I was going to escape without having to participate in what I regarded as a monstrosity. Unfortunately, Lloyd decided I should join in on the gang vocal shout of “Budweiser!” so I found myself swaying in front of the microphone and lip-synching the shout every time the cue came up. Lloyd, who maybe wasn’t as dumb as I remember him, kept telling me to get closer to the mic, because he couldn’t quite hear me.

It took about six hours to record the 60 second spot, and this is what we had when we were done:

18 years have passed, but my skin still crawls when that plays. I really do think it’s an abomination, and it amazes me that anyone thought it would help sell cans of beer. It makes me hate my band. It makes me hate myself. It sounds cheap, dirty, and stupid.

Which may be why it played endlessly on radio, all that year and into the next, on top 40 stations as well as the Modern Rock stations toward which it was originally aimed. And every time it did, each band member, including myself, earned residuals. The checks arrived very regularly, and they were very large.

I had considered the advance blood money, and briefly flirted with the idea of spending my share buying hundreds of cases of Molson Golden, the beer I actually drank back then. But my New York apartment was tiny, and they wouldn’t all have fit. So I gave it to charity, instead.

I didn’t touch the residuals, either, though I did rationalize that leaving all that money in the band account to fund gear, and recording, and touring expenses, was somehow non-evil.

While it wouldn’t be possible to overstate my continued disdain for the jingle, I am deliberately stressing my low opinion of it, and my ongoing qualms about the money it earned, because I’m going to spend the rest of this presentation trying to convince you of two things: the first is that my feelings are both very real and completely justified. The second is that those feelings are wildly wrong.

It took me 30 years to figure this out, but I’m pretty sure the change in my thinking is based on a better understanding of what music is for, and that this change mirrors an evolving acceptance of brand sponsorship among alternative bands and their fans.

Important fact #1: each band member earned enough royalties individually as a result of that little jingle getting played throughout 1992 that, for the first time ever, we all qualified for health insurance through AFTRA.

For me, that health insurance led directly to one very profound result: Abby Quirk, my spokes-model today.

I can state this categorically, and you don’t need to be embarrassed for her because she’s been hearing me say this for almost 17 years, now: if my stupid band hadn’t done that awful commercial, my daughter wouldn’t exist.

Basically, Budweiser bought my baby. Too Much Joy had been signed to a major label for three years when we did the jingle, but those residuals marked the first time we hit the earnings threshold necessary to get on the union health plan. My wife and I had been talking about getting pregnant, but hadn’t wanted to embark on that adventure while uninsured. Though I never cashed Anheuser Busch’s checks for myself, their mere existence literally changed my life (and created hers).

So, it is possible for me to say two seemingly contradictory things: I still hate that jingle, and yet I’m very, very glad we did it. Punk rock ideals are nice. But living, breathing human beings are possibly more important.

Clearly, parenthood mellows you. And it’s always easier to compromise when you can blame it on your kids. But I’m pretty sure the reasons I say I’m wrong to be such a diva about the ad apply even in the absence of children.

Because here’s important fact #2: as much as I detest the taste of Budweiser, and as lame as I think that jingle is, they offered us a far better deal than we ever got from any music company.

It’s kind of amazing, when you think about it. The publishing deal we signed with Virgin got us a quarter of a million dollars, which was sweet, but we traded 50% of all future publishing royalties in exchange. And our major label deal provided advances of almost $500,000 for three different records, but that money all got spent making the records, which the label owns in perpetuity.

Anheuser-Busch, and other brands, are different. They don’t want anything more from musicians beyond a few moments basking in our glow, in the hopes some coolness rubs off on them. Sure, some of their lameness rubs off on us in the transaction, and the psychic scars may never heal, but they pay handsomely for the privilege of briefly pretending Bud isn’t horrible.

In my experience, sponsors demand less from and give more to musicians than labels or publishers. So why was I giddy when I got signed, but ridiculously conflicted about lending my efforts to a brand campaign?

My reservations probably sound weird to fans of genres where sponsorships are badges of success. Even among rock fans they may just seem quaint: the Clash are selling Levis, Bob Dylan’s selling lingerie, insert your own unlikely example here.

But for the longest time, this just wasn’t done.

My first hint that something beyond my former high opinion of myself was changing came in 1998. Two strange things happened while I watched TV one night. The first was hearing the Who’s “I Can’t Explain” in a commercial for the Ford Taurus. This seemed odd, because I was pretty sure Pete had once sworn no sponsor could pay him enough to deal with the venom and bile Who fans would hurl at him if he ever allowed such a thing. Also, the connection between the song and the four-door sedan it was endorsing felt strained at best (although I think the announcer did say something about how Ford’s competitors “can’t explain” why their cars aren’t as good).

The second, even stranger thing happened just after the commercial ended. Or didn’t happen, to be more precise. I sat there, waiting to feel angry, or betrayed, or something. I mean, Pete Townshend was a childhood hero of mine. What was he doing shilling for my dad’s car? Surely, this called for some kind of reaction. But it turned out I just didn’t care.

Please note that my lack of reaction was not connected to my own misadventures in sponsorship land. In the intervening years I had maintained my ability to get righteously angry when bands I admired sold their music to advertisers, and I’d developed a tortured “tiers of terribleness” system to justify my hypocrisy. The bottom, and most forgivable, level belonged to developing acts who’d done what I had: lent their voices or even their names and likenesses to a sponsor. It was still wrong, but newly understandable.

The next tier was for developing acts that went a step further, and let the sponsor use one of their songs. It’s easy to be sponsored by no one when you’re Neil Young. It’s harder when you’re Luna, so I was actually kind of happy when I heard a snippet of one of their songs in an ad launching a scent by Calvin Klein, because I was pretty sure they were getting more out of the transaction than he was.

Perhaps this calculus was more informed by my own experiences than I was ready to admit, but at least it had an internal logic: there was a dividing line before which the artist was taking advantage of the man, and beyond which the man was ripping the artist off.

And that logic insisted there was a ninth circle of hell that belonged to established musicians who thought the songs they’d given to us still belonged to them, and that the rewards we’d bestowed on them already weren’t enough. That just seemed greedy, and inconsiderate. I still remembered the sense of betrayal I’d felt in the ‘80s when Lou Reed lent both his rock and roll animal persona and his song, “Walk on the Wild Side” to Honda for a series of TV and print ads pimping a fucking scooter!

Because it would take an entirely different 20 minute paper to explain all the ways an ad like that made the world a worse place for everyone, including Lou Reed, I will focus solely on the painful transition from documentary-like shots of the squeegee men and graffiti-ridden trucks that were actual facets of life in 1980 Manhattan to the well-lit dude playing the sax break from Lou’s biggest hit, because crap like that only exists in dreams, and the actual dreams of actual people are way more complicated and weird and get MORE disturbing as they progress, not less, and the thing that’s persistently terrible about even well-done television commercials of this type is that they hijack our subconscious and try to convince us that our frightening brains can be tamed if only we buy this one particular THING.

This is a lie, of course, but I believe the lie is easiest to see in older ads, because television advertising is an arms race with our own sense of sophistication, and the more sophisticated we think we are the savvier advertising has to get to win us over to its point of view. This spot was fairly cutting edge back in 1980, though it feels arcane today, given how ham-fistedly it cuts to Lou.

Yet the fact that Lou Reed is in this ad is not the point of this ad. He’s just like the squeegee men and the graffiti on the truck: a symbol of dirty city living. The fact that Lou is hawking scooters is no more ridiculous than the fact that every shot we’ve seen before was leading to a shot that posited scooters as the culmination. It’s kind of weird that he’s in the ad, but it’s actually less weird than everything else the ad is trying to talk us into.

Here’s something important my Budweiser jingle experience taught me: there’s no faceless conspiracy of Mad Men deliberately co-opting icons of rebellion and turning them into mouthpieces for the status quo. My band got our ad because two dudes at the agency were fans, and figured we could use the money. They thought they were doing us a favor. I assume the dudes working for Honda were thinking the same way.

Because most people who saw that Honda scooter ad had no idea who Lou Reed was, even if a good deal of them had heard “Walk on the Wild Side” at some point in their lives. That might be part of what makes fans so upset when their personal heroes’ music appears in commercials: the music is by definition not the most important thing there. It’s being harnessed to celebrate something beside itself. It’s literally diminished.

Almost 20 years later, stuff like this had lost the power to offend me. Or, if advertising is an arms race, maybe it’s more accurate to say musical commercials had gained the power to neutralize my offense mechanism. And one way they did this was by seeming to honor the music they used.

I can’t embed this one for some reason; click the image and it will launch the clip in another window

That’s Luscious Jackson, in one of a series of well-received Gap ads from the late-‘90s. I assume you agree with me that it somehow feels less embarrassing than the Lou Reed spot, right? I mean, it’s just a band playing one of their tunes. Maybe you don’t know the band, and maybe you’re not sure what they’re advertising, but those mysteries kind of draw you in.

But perhaps you also share my lingering sense of unease. Something isn’t quite right, and I don’t mean that the song is obviously longer than the 30 seconds it lasts here. The band just looks too uncomfortable when they play the notes to the old jingle, “Fall in to the Gap,” at the end there. It’s unclear whether they always look that awkward when they’re not playing music, or if they’re simply realizing they’ve gone one step too far.

This was just one of many examples at the time of bands I loved cropping up in ads for brands I did not. I was curious enough about the phenomenon to track down the people responsible and ask them, as non-judgmentally as I could manage, what they were thinking.

Luscious Jackson’s singer, Jill Cuniff, explained they took the spots more for publicity than for cash, as the band had spent a wearying year promoting their last album, and still hadn’t broken out to a wider audience. “We ended up promoting ourselves as much as the Gap,” she insisted.

Michael McCadden, the Gap’s head of Marketing, concurred, telling me, “TV Guide wrote an article about the campaign, and they showed a picture of Luscious Jackson, and the whole thrust of the article is who are these cool people in this Gap campaign? We heard about radio stations across the country getting calls, ‘Can you play whoever that all female group is in the Gap campaign?’”

Both Cuniff and McCadden felt the trade was fair, but things still felt unbalanced, to me. McCadden didn’t help matters by explaining how the band’s outfits were chosen: “They did go to a store, and they sort of told us what they really liked, we also brought a lot of clothes, and then we worked with them to make their outfits really what they would wear.”

“We worked with them to make their outfits really what they would wear.” Not what they DO wear, mind you, just what they WOULD wear, you know, if they were gonna be in a Gap commercial.

If you’re an SVP of Marketing, it’s your job to say things like that with zero irony. I was more taken aback by Cuniff’s similar lack of irony when explaining she knew she did the right thing because “our publicist’s very concerned with our image,” and the publicist said it was a great idea.

“We said to ourselves, ‘Here we are. We’re in the marketplace. Is this stepping over a line?’” They didn’t think so: they liked the campaign’s simplicity, and the fact that it looked like a music video. A deciding factor, in Cuniff’s words: “There was not a lot of room to look like a cheeseball.”

That felt like an important insight: their decision was largely driven by production values. As of 1998, doing a commercial was no longer unthinkable — just doing a cheesy one.

Well, production values are better than no values at all. And Luscious Jackson turned out to be pretty prescient, as TV commercials are now considered a legitimate source of new music discovery, and artists fall all over one another competing for the chance to be in a spot like this one:

That ad did wonders for Feist’s career – the track it used went from selling 2,000 copies in a week before the ad aired, to 73,000 after.

The spot also seems like a pretty natural evolution from Luscious Jackson’s Gap ad 13 years ago. Both take a minimalist approach. Both present the artists ostensibly being themselves. Both tease you with a snippet of a song that is much longer in real life. And both try to make the connection between band and brand as natural as possible. The Nano ad just does it all a lot better.

It helps that the ad’s showing an actual Feist video. And it helps that one of the actual functions of the device being advertised is the showing of videos. You can’t get much more aligned than that. Spots like this may be the closest artists can come to preserving everything fans value about their music while also earning serious dollars and, not incidentally, exposing themselves to new fans.

Sara Bareilles quickly proved Feist-like bumps are repeatable when she lip-synched “Love Song” in a Rhapsody commercial:

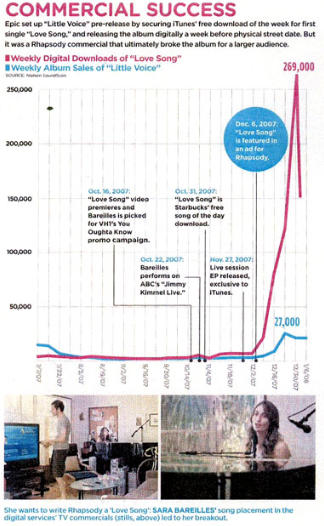

A chart Billboard ran after the fact demonstrates the ability of commercials like this to break developing artists with mainstream audiences:

In two weeks, “Love Song” leapt from sales in the low thousands to 269,000. No promotions before that had anything close to the same effect.

Duh. TV ads work. We’ve known this for at least 50 years. What’s new is that they’re now working for musicians, not simply because of them.

None of that means we’ve reached some uncomplicated nirvana where artists get to be pure AND rich. It just means that things have changed, and at least one or two of those changes are for the better.

It means not every single ad with a song by an artist you love automatically sucks. It means some artists in some ads are getting more than money. It may not ever mean the music in an ad is the most important thing, but it suggests that music can sometimes be just as important as whatever’s supposedly being advertised.

It’s possible we have the arms race to thank for this development. My assumption that the artists can sometimes tie, if never win, may just be the latest example of Madison Avenue’s ever-increasing sophistication at feeding us the illusions we crave.

But I stand by my assertion that bad advertising hijacks our subconscious, whereas music’s job is simply to explore that subconscious. So when I see advertising in which music is forced to hijack rather than highlight, I am saddened, even if I understand the factors that made the musicians in question agree to have their art used in that way.

Whereas any time I see a commercial that leaves the music alone to weird us out however the music wants to, I am happy, because I’m pretty sure that by setting the bar higher it will result in less advertising that makes me want to kill myself.

And there are still far too many ads like that. They’re so easy to find that I’m going to play us out with one that’s only two weeks old. It aired during this year’s Grammys, and is notable for making even WORSE use of “Walk on the Wild Side” than Honda managed oh so many years ago.

Apologies for leaving you with an awful commercial instead of a non-detestable one, but we should recognize and reward ads that showcase music without diminishing it, and there’s no better way to demonstrate WHY than reminding you what the alternative is.

I found this because I’m listening the the King Biscuit Rolling Stones broadcast from 1987, which features the wonderful Bo Diddley singing for Bud…and also the Meters, although I’m not sure if it’s the Meters, or it it’s a studio imitation. I love the Bud commercials…Joe Jackson, Toots Hibbert, Icicle Works, Dexy’s Midnight Runners….all great bands…and their commercials were wonderful.

I played the Mabuhay Gardens…and then had a career in advertising. Advertising paid for my two children, not the 1/3rd we got of the door at the Mab.

I should have been clearer: I ran a search for Budweiser Beer rock radio ads, and found your wonderful essay.