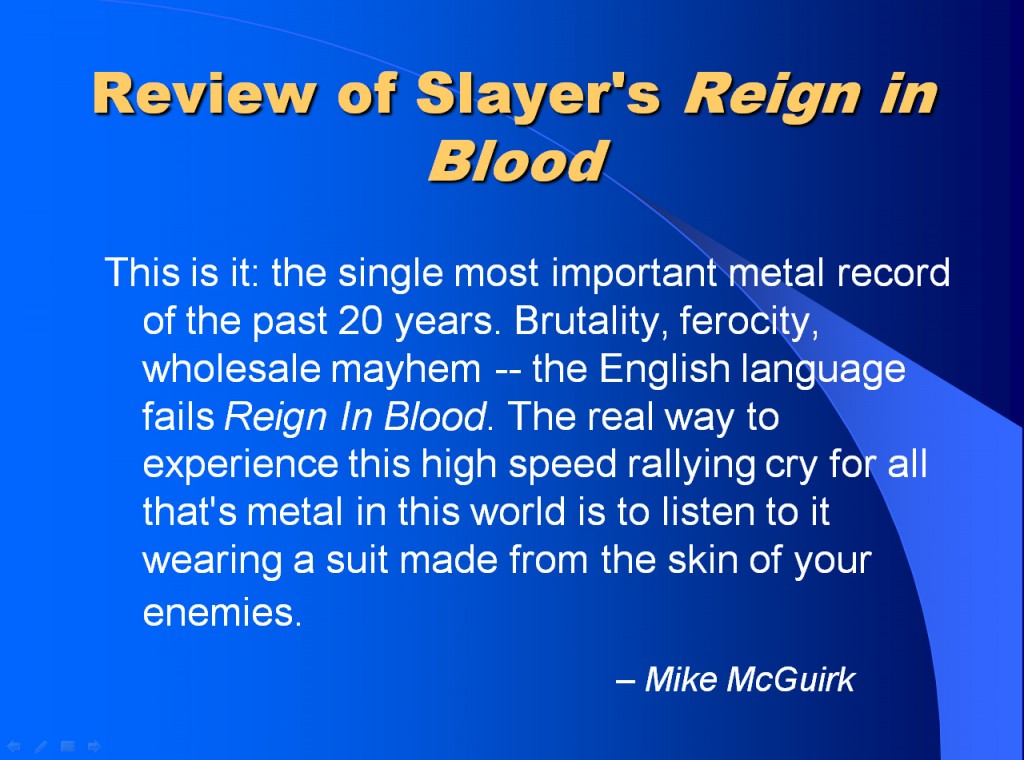

I read this at the 2006 Pop Conference in Seattle. When I was finished, Robert Christgau ran up to me and said, “Who is Mike McGuirk and why haven’t I heard of him?” The answer to the first half of that question is, “The best natural music blurb-er I’ve ever seen.” The answer to the second half is a mystery even to Mike, I think.

I read this at the 2006 Pop Conference in Seattle. When I was finished, Robert Christgau ran up to me and said, “Who is Mike McGuirk and why haven’t I heard of him?” The answer to the first half of that question is, “The best natural music blurb-er I’ve ever seen.” The answer to the second half is a mystery even to Mike, I think.

Like, I assume, most of the people at this conference, I have what average citizens, upon entering my home or office, almost always declare to be a frighteningly large music collection: LPs, CDs, cassettes, hundreds of gigabytes of mp3s scattered across an array of hard drives and portable devices — it all gathers in piles both physical and virtual wherever I spend serious time. When these average citizens are new or casual acquaintances, they often move from commenting on the vast and tottering nature of the stacks of discs to making deductions along the lines of, “You must really like music, huh?”

I almost always reply with a semi-embarrassed, “Kind of,” which is the most honest answer I can give. Though my collection is indeed larger than the average citizen’s, it’s far smaller than that of most of my music geek friends, and the reality is I hate far more music than I like.

I take it for granted that most people who make or write about music – or any other art form, for that matter — would say something similar, if pressed. 98% of everything is crap, but the 2% that isn’t makes wading through all the shit worthwhile, and encourages you to hoard the good stuff when you’re lucky enough to find it. It also makes you want to sing the good stuff’s praises, as loudly as you can, and press it into the hands of anybody you can convince. If more people knew about it, after all, maybe they’d stop playing all that crap you can’t seem to escape, no matter how hard you try.

I’m lucky enough to have a job that gives me ample opportunity to do just that: Rhapsody is an online music subscription service that gives customers instant access to almost 2 million songs they can play whenever they want, as often as they want. And the editorial team’s job is to help our customers navigate through that wealth of material without making them feel overwhelmed. Fun as it is to tell people about your favorite new discoveries, it’s far more satisfying giving them the ability actually to play the things, then smile and nod their heads and start looking for more stuff just like it.

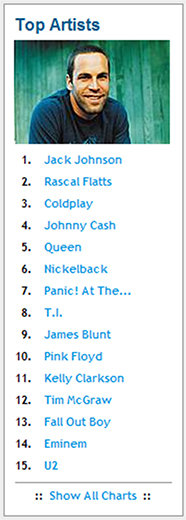

Naturally, as with any honest democratic endeavor, there’s a catch. The 2% of brilliant stuff that I worship doesn’t always overlap so neatly with the 2% of stuff individual customers happen to love, and the most forceful evidence I have of this fact

is that Jack Johnson has been stuck at the top of our charts for over 2 months now.

Now, the same part of me that wanted to grab every last one of our customers by their metaphorical lapels and not let go until they agreed to listen to the Hidden Cameras feels an equally strong compulsion to grab those same people by those same imagined lapels and ask them what the fuck is wrong with them, surely they realize they are doing themselves and possibly our very nation serious psychic damage with all that goddamned Jack Johnson.

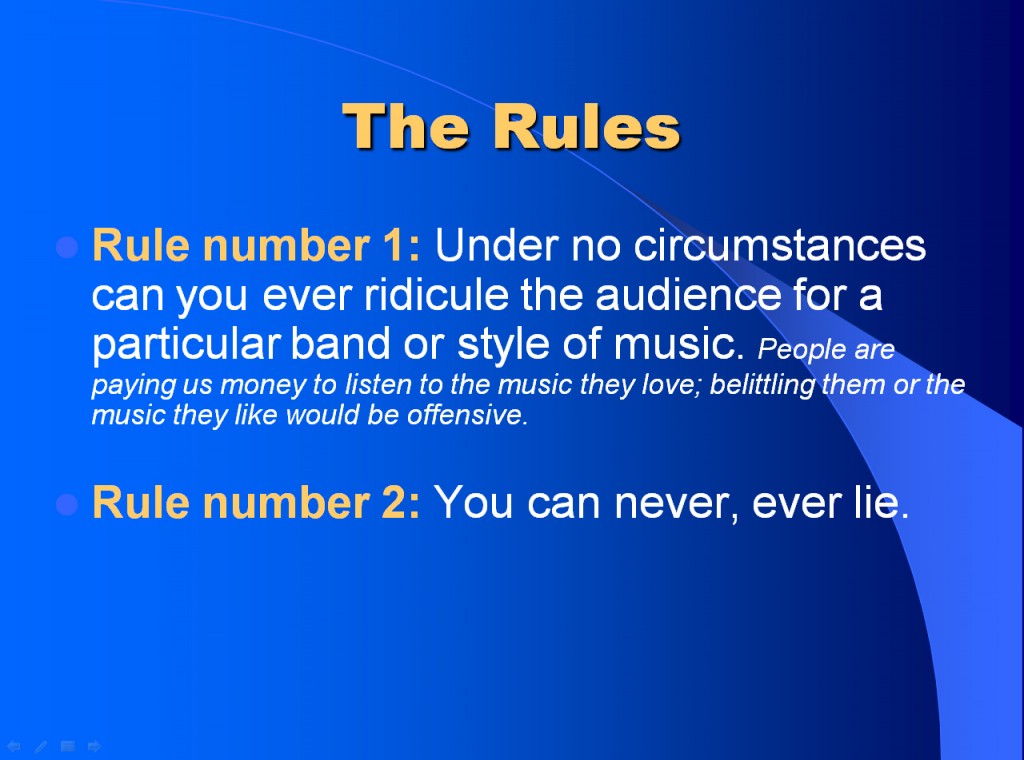

However, we have Rules. These Rules insist that the first impulse is pure and healthy and good, and, not incidentally, makes fine business sense, while the second impulse is not just inadvisable for corollary fine business reasons, but is also morally indefensible. I wrote these Rules myself, and I am going to attempt to convince you that I was not only right to do so, but that accepting these Rules makes you a better critic, and possibly a better person.

First, though, I should admit that I ran this thesis by the writers who must abide by these rules on a daily basis, and though their replies were invariably diplomatic, I think it’s safe to say that most of them would claim that we don’t really do criticism at Rhapsody. This disturbs me, partly because it means that a conversation I’ve been having with my staff for five years running is nowhere close to finishing, but mostly because it says something kind of frightening about just how stubbornly ingrained in our culture some (I submit) nutty notions about what criticism is have come to be.

We’ll get to all that soon enough. For now, let me lay out the rules. There are only two of them, but they’re doozies:

Like I said, I’ve spent the last five years trying to convince a bunch of brilliant, funny, knowledgeable and passionate music writers that these two rules are NOT mutually exclusive. And it looks like I’ve failed, but they do me the courtesy of abiding by the rules, anyway, if only because I’m the boss.

Here’s how the rules play out in practice: when writers think a particular artist or album or song is the bee’s knees, they’ve pretty much got a free pass to communicate that enthusiasm however they see fit.

It’s only when they find themselves dying to trash something that we ask writers to take a deep breath and analyze why they’re having that reaction. It’s easy to forget there’s a difference between how music sounds and how it makes us feel. And because space is so limited in Rhapsody, it can be extra tempting to declare one’s opinions as though they are facts and leave it at that, with no other context or explanation. We insist our writers not fall into that trap.

Does that mean it’s forbidden to say anything bad about any of the music in Rhapsody? Not at all – it just means our writers have a responsibility to make a clear distinction between objective facts about a given piece of music and their subjective opinions about that music (and, wherever possible, to provide a context for their views).

That doesn’t strike me as a particularly controversial request. In fact, I feel kind of dumb having to say it out loud – you’d sort of think any thoughtful writer would have internalized that approach early on in his or her career, and turned it into a habit that happens without thinking. But the vigorous resistance I’ve encountered among my own editorial staff, coupled with the sniffing dismissals I sometimes get when I discuss our approach with critics who work in different forums, convinces me this stuff is worth talking about.

Granted, the editorial in Rhapsody serves a very particular and somewhat abbreviated purpose. Since we’re writing what amounts to independent liner notes for whatever percentage we can cover of almost everything ever released, staff members rarely get to pick and choose what they’re asked to analyze. That same wealth of material doesn’t leave much time or space to expound about any one item: we simply don’t have much to spare for the qualifying clauses or straight biographical details that could otherwise be used to defend, couch, or outright mask dismissive opinions. If you tell writers they have 50 words to describe a new release, and they regularly devote 45 of those words to detailing just how much they dislike it (mind you, not why, just how much), you’re left with the conclusion that most music writers feel this sort of info is the most urgent thing we have to get across. And before you get around to wondering why that might be and what it might say about us, your first task is to figure out a way to break the habit.

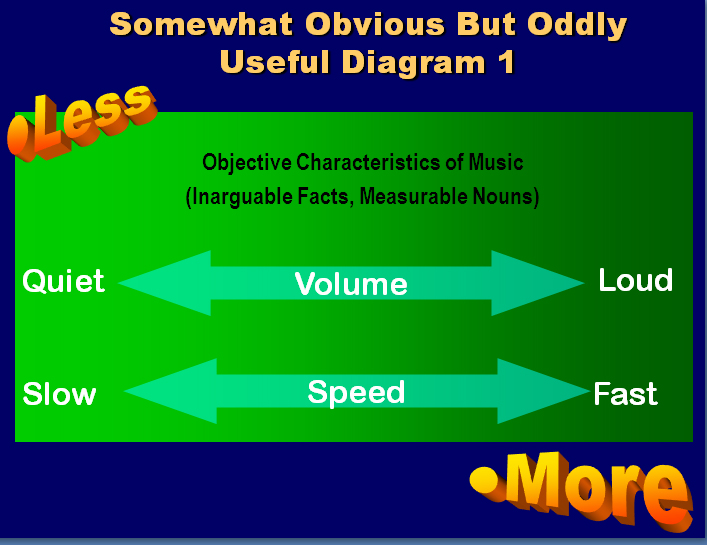

So, apologies in advance for the remedial nature of what follows – this is the primer part of the presentation. If it seems overly obvious to you, congratulations; in my experience, you are the exception, not the rule, in 21st century U.S. popular music journalism. I will limit myself to two somewhat obvious but oddly useful diagrams, cut-and-pasted from Rhapsody’s worrisomely large Editorial Guidelines document, which is not so much an instruction manual as a record of the ongoing debates the staff has had about the approach we take and why it may or may not be reasonable.

Once you get in the habit, spotting the objective characteristics of a work becomes pretty easy. They’re anything you can measure, anything you can state that no one in the world, from Asia to Antarctica, is going to contradict. You can measure the tempo of a song; you can measure its volume. These are inarguable facts that let you pinpoint precisely where on a given scale a particular piece falls. (If you’re an academic, and you’re tempted to debate me about whether my objective facts are actually as inarguable as I say, please save it for the bar).

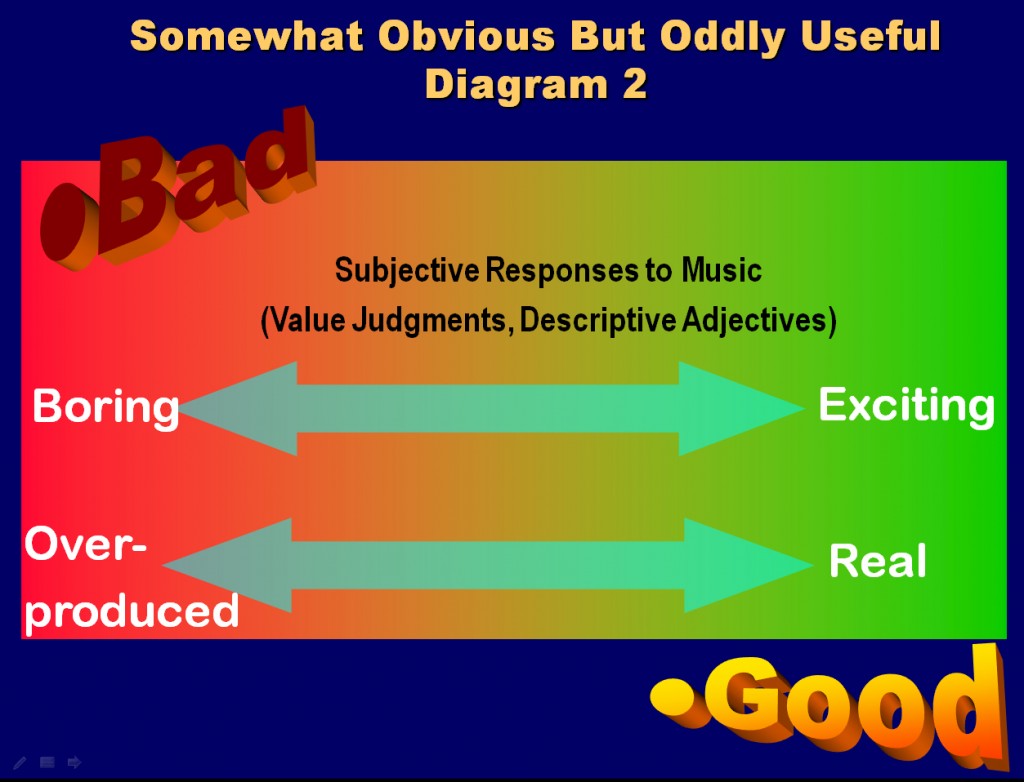

The important point is that any one listener’s reaction to those traits is going to depend on what he or she values most highly in music, and suddenly we’ve renamed our objective Less vs. More poles “Bad” and “Good.”

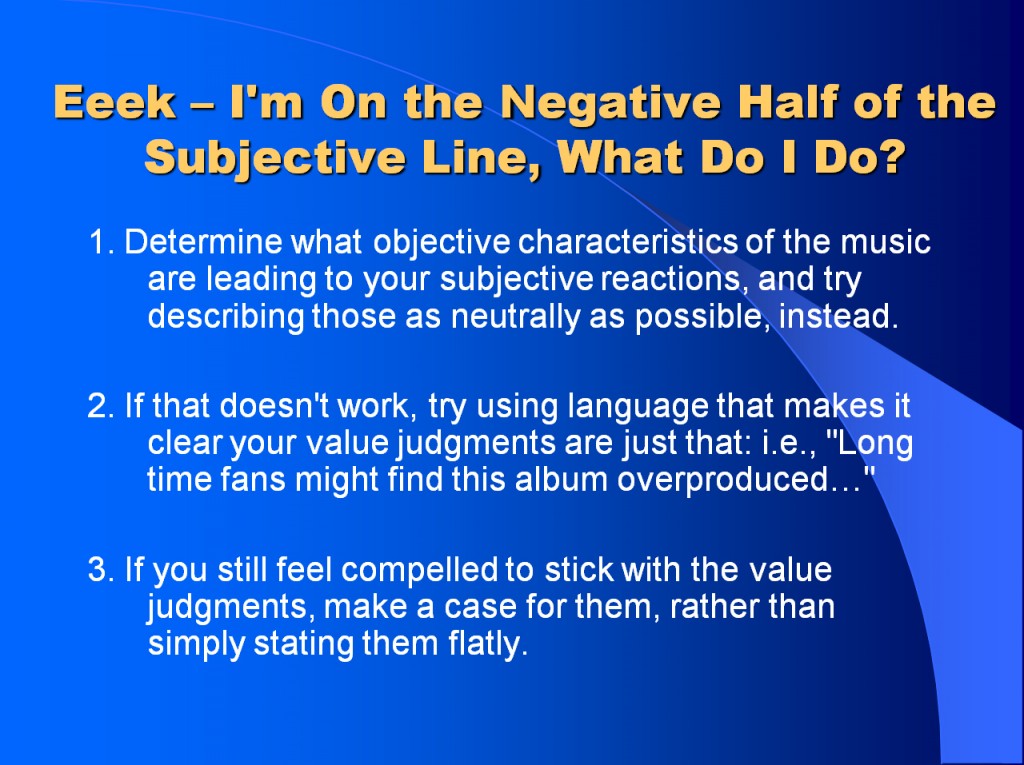

One person (or even the same person at different times) might find slow, quiet music boring, while another finds it incredibly moving and beautiful. So, whenever writers find themselves thinking or writing on the negative end of the subjective line, we ask them to take a moment to ask what about the music is provoking that response in them. For instance, say they find a new record by a group they like “overproduced.” That’s a value judgment – so what’s the objective characteristic of the music that leads to that particular feeling?

Sometimes, the way they answer that question provides important clues about the ideals against which they’re judging the music. If one writer values studio albums that capture the energy of live performances, she may be evaluating the record on its “liveness,” whereas someone else who values technical expertise could hear the exact same thing that writer called “overproduced” and praise it as “professional sounding.” Objectively, they’re both evaluating the same thing, but the way they define it determines what ends up on the positive end of the spectrum.

Again, negative value judgments aren’t prohibited when writing for Rhapsody; they’re more like flashing yellow lights. Whenever you see one, we ask you to slow down and do the following:

There’s a fourth step, when even #3 proves unworkable, which is to trade assignments with someone sitting next to you. Happily, we don’t have to go to step 4 all that often.

There’s a fourth step, when even #3 proves unworkable, which is to trade assignments with someone sitting next to you. Happily, we don’t have to go to step 4 all that often.

I’m not pretending it’s easy or even particularly fun to take this approach when you can make just as little money for other outfits being a snarky bastard and pretending your tastes are the only valid ones. But I do believe pretty firmly that taking this approach makes you a more honest and disciplined critic. More importantly, it doesn’t have to lead to dry, passionless descriptions of what something sounds like. It leaves plenty of room for skilled writers to communicate what the music means, to them and to others, even when those meanings diverge. If you can master this type of thing using just 375 characters (including spaces), you’re a pretty rare beast.

So, a couple of quick examples in which the Rhapsody staff adheres to these guidelines, writing about music they might personally find distasteful without lying OR unduly pissing off people whose lives are given meaning by the likes of David Coverdale.

Sometimes, a just-the-facts-ma’am approach is all you need, as in this biographical tidbit about Il Divo:

The writer in this case said she was originally tempted to insert such modifiers as “cloying, melodramatic, puke-inducing, saccharine” when describing the group and its work, but she told me everything I personally needed to know with the bit about classing love ballads up by translating them into Portuguese. Meanwhile, if my sister-in-law reads this blurb, she’s highly likely to shout, “Goodie!” and start listening. And that, frankly, is the mark of successful Rhapsody writing: it recognizes that the adjectives we choose often say more about ourselves than the work in question.

Generally speaking, when you encounter nothing more beyond a straight recitation of facts in Rhapsody, it’s a safe bet the writer is holding his or her nose with one hand and typing with the other, because we only go there when we have nothing more useful to add. But just because we prohibit our writers from ridiculing music certain customers might like doesn’t mean we’re mindless cheerleaders for everything in our library. Other writers find ways to communicate their personal distaste without implying the world should share it.

It’s possible this one is so sneering in its appraisal that it’s just a way of spelling “crap” with 300 letters, but that’s actually kind of my point: if you think I shouldn’t like something, I need to know why, and it helps to have a general idea of the types of things you think I should like, too. This writer has given me a pretty good sense of what he values and made it clear this particular record doesn’t measure up, while still giving me something to listen for should I choose to play it anyway. That’s a hell of a lot of info for one little blurb to boast, and it manages by obeying both our rules: it doesn’t lie about how the author feels, and it doesn’t ridicule me for disagreeing.

That snippet and the next one were both written by our Rock editor, Mike McGuirk, who’s uniquely talented at this sort of approach even though he frequently chafes against it by sending his editors blurbs that effusively praise artists he obviously despises. But usually he just finds the common ground players and haters can all agree on and somehow makes you admire both him and the artist in question for that, as in this excerpt from his Whitesnake bio:

Other writers confront their confusion head on and find it can’t withstand a (somewhat) more considered appraisal of the work in question.

You may have noticed that none of these blurbs is 100% guaranteed to please every customer. That’s not our job, and it wouldn’t be possible even if it were: personal tastes are so charged that even when we think we’re being admirably objective it’s easy to infuriate people. (Really: we’ve had bands threaten to sue us for describing their music as “guitar-driven”). So, while rule #1 may sound like it’s designed to serve our audience, that’s a secondary benefit, not its primary purpose.

Remember, rule #1 doesn’t say we have to validate contrary opinions, simply that it’s pointless to dismiss them, and I selected the examples that I did mostly because I think they let you sense how sorely tempted the writers are to do exactly that.

Which begs the question I deferred earlier: what does it mean when writers feel dishonest if they don’t tell you precisely how good or bad they find a particular artist or piece of music? I’ve got a semi-harsh answer: it means most writers are lazy. It means most of us begin from a stance that our subjective reactions to a given work have the weight of universal truths, and we have little duty or obligation to convince anyone else why this is so. You either share our tastes or you don’t, and if you don’t it’s probably just because your record collection isn’t as big as ours.

Also, I think, there’s a subconscious fear that everyone else (or at least everyone else whose opinions we happen to care about) acts the exact same way, so god forbid they misinterpret our writing to mean we actually enjoy John Fucking Denver. That is, a lot of times we’re less concerned with letting people know what we think of them than we are with making sure no one thinks that way about us.

Rhapsody’s editorial guidelines basically say screw that. Rule #1’s main purpose is to kick a useless crutch out from under the arms of folks who’ve gotten accustomed to ambling along at too leisurely a pace, while rule #2 just says you have to keep going till you get to the center of whatever it is you really think. Together, they force you to append “because” to any sentence that begins “I think this,” and insist there should always be an unspoken, “of course, I might be wrong” at the end.

Here’s the uplifting part: awkward and objectionable as many people who care deeply about music initially find this approach, it can prove oddly liberating, and has all kinds of other useful applications in the real world.

The first is that it discourages using your opinions as a way to pre-empt conversations, and substitutes the notion that you can invite disagreement without undermining your own convictions. This is mostly a matter of recognizing that you’ve got a better chance to move Ashlee Simpson fans onto artists you consider more edifying if you don’t introduce yourself by barfing all over Ashlee.

The second is pretty closely related to the first, and is seriously the most valuable thing I’ve gotten out of working for Rhapsody, stock options notwithstanding: it moves you from dividing the world into people who like the same kind of music as you do and everyone else, toward dividing the world into people who like music just as much as you do and everyone else. While both groups will probably always be smaller than you want them to be, the folks who share your passion for music are always going to outnumber the folks who share your precise taste in music.

Since everyone could use more friends, that’s as good a place to start looking for some as any I can think of. Plus, I have a feeling we’d have a lot more folks who like music as much as we do if the rest of us just stopped intimidating them because we’re so damn insecure.

I might not like Nickelback, but boy would I love to have a beer with the fan who was moved to write in and tell us we’re brain dead because we dared describe the band as “post-grunge.” I admit I think his objection is ridiculous, but I also accept we failed to convince him we have any moral authority to critique the music he likes, and I would welcome an opportunity to get drunk with the dude and attempt to do a better job. The fact that he cared enough to write implies we’ve got SOME common ground, and the additional fact that he knows how to spell and use the shift key suggests I, personally, might actually get along with him.

I might not like Nickelback, but boy would I love to have a beer with the fan who was moved to write in and tell us we’re brain dead because we dared describe the band as “post-grunge.” I admit I think his objection is ridiculous, but I also accept we failed to convince him we have any moral authority to critique the music he likes, and I would welcome an opportunity to get drunk with the dude and attempt to do a better job. The fact that he cared enough to write implies we’ve got SOME common ground, and the additional fact that he knows how to spell and use the shift key suggests I, personally, might actually get along with him.

There’s a final benefit of this approach I can acknowledge only as a reasonable possibility, but can’t verify as a fact, since I haven’t quite gotten there myself. Still, I’m pretty sure it’s worth working toward: the end of musical shame. I don’t know about you, but I don’t really want to be embarrassed by anything I listen to, or think I’ve made someone else feel that way, even if it’s Jack Johnson they love (and I really hope there’s someone in this room who likes Jack Johnson, so he or she can tell me if I sound like I mean this part, because I do, but I don’t know if I sound like I do, and I want to). I hate the idea that there are right things to think and wrong things to think about any particular work of art. Surely some opinions are more or better informed than others, and yes, I and presumably, therefore, others, can always be swayed by impassioned and/or well-reasoned arguments, and, duh, I want to know if my enjoyment of something is the nefarious result of forces more cynical and manipulative than my naïve brain can credit, but can we maybe admit many if not most of those occasions are the exception, not the rule? That generally speaking the impulse to bang two rocks together while howling is an enlightened alternative to banging one rock against someone else’s skull while howling because that skull thought something different than yours did?

Please understand, I am not really a kum-ba-ya type person. My inability to speak with strangers for extended periods of time without making one of us want to punch the other in the face is the source of much amusement to those few people who resisted that initial impulse and eventually got invited to my house, and saw the tottering stacks of CDs, and said “You must really like music, huh?” and understood, or pretended to, or somehow ignored me without being rude when I said, “Kind of,” and who I now count among my close friends.

Even though most of them like shitty music.