This presentation from the 2007 Pop Conference was oddly controversial, in that during the Q&A I was taken to task for supposedly lauding a future full of white guitar players. If you think the paper’s title is one more example of cloistered music critics privileging indie rock, well, then my saying “Good News For Yo La Tengo just sounds funnier than Good News For Luther Vandross” probably isn’t going to change your mind. But the point remains that the examples that follow have analogs in every genre. I do think Indie Rock is more prone than most genres to view a gap between critical and commercial success as something desirable, though, so I’m particularly interested to see what happens if/when there are more than just psychological rewards for being a critic’s darling.

presentation from the 2007 Pop Conference was oddly controversial, in that during the Q&A I was taken to task for supposedly lauding a future full of white guitar players. If you think the paper’s title is one more example of cloistered music critics privileging indie rock, well, then my saying “Good News For Yo La Tengo just sounds funnier than Good News For Luther Vandross” probably isn’t going to change your mind. But the point remains that the examples that follow have analogs in every genre. I do think Indie Rock is more prone than most genres to view a gap between critical and commercial success as something desirable, though, so I’m particularly interested to see what happens if/when there are more than just psychological rewards for being a critic’s darling.

I am here to make some proclamations about the future of the music business. I should provide a couple caveats at the outset, however. First, I will confess I’m not 100% sure whether what follows is a prediction or a just a wish. I’m pretty confident (so, like, 99%) it’s the former, but I offer that 1% of doubt as a little place of refuge anyone who disagrees with me can go try to build a city where all the citizens do their best to keep the existing, depressingly diseased music business functioning as-is indefinitely. Good luck with that.

Second, I will acknowledge that the consequences of my being wrong are pretty damn slim. Since I think the changes I foresee will take another ten years or so to be incontrovertible, it’ll be 2017 before anyone who hears this can laugh at me if what I say today turns out to be moronically misguided..

Third, and really most importantly, I should stress that, like every musical revolution I have had the pleasure of living through so far, its ultimate effects will be both way more subtle than anyone’s imagining right now, but also profound in ways that won’t be fully recognizable till it’s over. Since my music-freak phase didn’t start till the late-seventies, I have only been able to read about Stravinsky-inspired riots, the rise of radio, the decline of Western civilization heralded by Elvis, the shift from singles to LPS, and all the naked drug-taking hippies whose music stopped the Vietnam war, but I have a feeling you could say the same thing about them: the shit that seems completely groundbreaking at the time quickly reveals itself as a fad that gets replicated incessantly till everyone gets bored and moves on to something else. And that’s when people start to realize something more fundamental has changed while they were watching what they thought was the show.

Since online music clearly represents one of these seismic shifts, it follows that whatever the prevailing wisdom is about what it all means is bone-headedly wrong. Here’s an example of what I mean: the notion that we are leaving a world in which people purchase albums, and returning to one in which people purchase singles. If anyone ever says anything like this to you, slap them for me.

Then say this: you’re an idiot. We’re already living in a world where almost nobody buys anything. And while that might well mean the end of the music business as we know it, it doesn’t mean the end of the music business. If we’re lucky and/or if I’m right, it means a new, better business that stops trying to convince ten million people to buy the same thing, and instead focuses on the things that individual people wind up listening to ten million times.

Here’s why: music is transitioning away from being a product that people buy in discrete units, and turning into a service, something that people access at will, whenever the urge hits them.

A final confession here: I get very annoyed whenever I read an article claiming people “own” music they buy through iTunes, but merely “rent” music they find in an online subscription service such as Rhapsody. I get annoyed because I don’t think you rent music through Rhapsody any more than you “rent” electricity. Music isn’t something people rent – it’s something people need. It’s just that, until very recently, they’ve never had the luxury of listening to anything they felt like if they hadn’t already bought it (or knew somebody who had). That’s already changed, irrevocably.

For more than half a century, the music business has relied upon two types of charts: airplay charts, which track the most popular songs being broadcast to people, and sales charts, which track the songs those people are then willing to part with hard-earned cash to own. Rising to the tops of these charts and lingering there as long as one can manage has generally been considered the best measure of a musician’s commercial success.

But that won’t be the case for long. If airplay charts represent what gets fed to the audience, and sales charts track what subset of that material the audience actually swallows, usage charts tell us what the audience manages to keep down. Charts from services such as Rhapsody make it possible to track exactly which songs people actually listen to over and over again, after (or instead of) buying new records.

Please understand, I don’t intend any of what follows as a commercial for my particular service. Most of my figures come from Rhapsody, because we already pay royalties every single time someone plays a song through us, and that means we’ve got an early glimpse into how such a set-up affects not just listeners, but the people getting paid for what they listen to. But whether or not the company I work for is still around in ten years’ time, I promise you that it will be so easy to listen to whatever you want, whenever you want, wherever you are, that the difference between owning music and just being able to access it will be minimal. Furthermore, the labels and artists who release that music will be earning more from such usage than they do from actual purchases of said music. Explaining exactly why and how that will happen would require a separate and, I think, less interesting 20 minutes, so for now let’s just pretend you’re convinced of this inevitability, too, and focus on what it might mean for the music that gets made in the future.

Here’s the most important thing we’ve learned so far: giving people a cheap and easy way to listen to anything they feel like significantly changes what they choose to listen to. Average citizens quickly become way more musically adventurous than you might expect. Most every subscriber will start by playing some tracks that are currently huge, but they all quickly disperse in random directions.

So, hits don’t disappear, but they do start to weigh a lot less. They become like the weather – the thing you talk about for the first five minutes when you meet someone new, before you find something you both care deeply about that can form the basis for a genuine friendship.

My four favorite numbers should demonstrate just how dramatic a change we’re talking about:

The first number, 48.5%, is the percentage of sales generated by the top 100 artists in a physical retail environment such as Wal-Mart. Almost half their sales come from a very small sliver of acts. That makes sense: when it costs a listener 10 or 15 dollars to try something, he or she isn’t all that likely to take a flyer on a band just cuz they have a cool name or the album artwork is appealingly weird. Also, the Wal-Marts of the world don’t stock the most awe-inspiring range of music to begin with.

As soon as you expand the selection and drop the price, in an online retail environment such as iTunes, customers get a bit more adventurous. Only 33% of iTunes sales come from their top 100 artists. Virtual shelf space means iTunes can stock just about anything, no matter how low the demand, and the $1 price point per track makes you that much more likely to plunk down your credit card, especially if it’s late and you’ve been drinking and just have to hear a particular tune.

On peer to peer networks, the selection is even more varied, and the price is as low as you can get: it’s free! Again, you see listeners branching out even more: according to my sources at Big Champagne, which tracks P2P activity, only 28% of the files traded in a given month come from the top 100 artists.

Rhapsody does even better in terms of music discovery: less than 24% of our total plays (and there are over a billion a year) come from the top 100 artists. This isn’t a demographic oddity, by the way: I’ve been tracking this number for three years, and I keep expecting it to rise as our subscriber base gets younger, more mainstream, and more fickle. But it’s held surprisingly steady, even as we’ve grown.

Now, maybe you think I’m cheating a little bit with that last number, since the first three stats measure how often certain things are purchased (or simply obtained), while the Rhapsody figure measures how often that music gets played. But the difference between those phenomena is the point I’m trying to make.

Think about your own record collection. No mater how big it might be, there’s probably a small subset of it you’ve returned to again and again; a slightly larger set you’re pleasantly surprised how much you enjoy those few times you do bother playing something from it; and then a ton of stuff you always ask yourself why you bought and if it’s even worth packing again every time you move.

Until very recently, such dilemmas were entirely your own – they weren’t the music industry’s problem, because, excepting those rare occasions when you listened to a particular LP so often you actually wore it out and had to buy a new one, the industry made the same amount from you whether you never got around to playing it or listened to it 1,000 times. Once you’d bought a particular album, their job was to figure out what else they could convince you to buy.

So…how might that equation change once they start getting paid on actual listens?

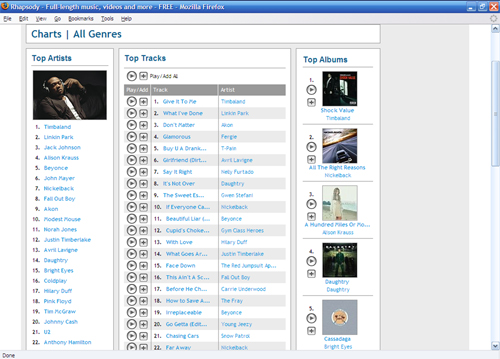

At first glance, Rhapsody charts don’t seem to diverge dramatically from what you see week to week in Billboard.

But those slots where we do split reveal a lot about the difference between songs you listen to because they’re in the air right now, and songs you listen to because you can’t stop, no matter how much time has passed. Lots of artists break into our top 5 for a couple weeks and then plummet. The truly massive acts – and, I submit, the artists the music business of the future will base itself around — are the ones who find a slot in the top 50 and hover there for years after anyone’s stopped talking about their last record.

Some of those names shouldn’t surprise you: the Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, Queen. Labels have been finding ways to re-sell us the catalog of these classic rock staples for years, and Dark Side of the Moon has been famous since the ‘70s for its ability to hypnotize new legions of listeners into buying it week after week after fucking week.

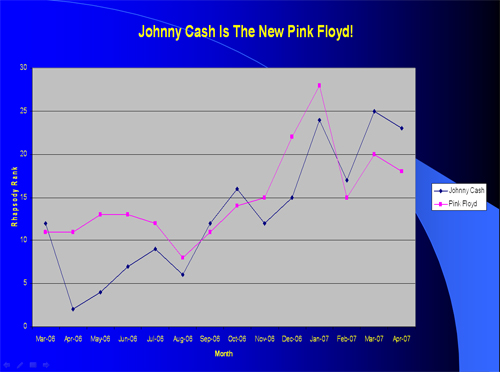

But Dark Side is usually held out as an exception, rather than a rule. The first amazing thing usage charts reveal is just how many Pink Floyds there really are. And the second amazing thing is that Johnny Cash is one of them:

Really. This guy is gigantic in almost the exact same way as Pink Floyd. And it’s not just thanks to hipsters who discovered him via Rick Rubin. Johnny Cash has been in our top 50 for years, and tends to bounce around in a range between #12 and #25, even when he’s not being portrayed by Joaquin Phoenix in an Oscar-nominated biopic.

Johnny Cash has several things that are necessary but not sufficient ingredients to mega-success in usage charts: the first is a deep catalog – the more tracks you have, the more chances people have to listen to you. The second is recognizable hits – like one of those insect-eating plants, these attract all manner of passersby, from folks who are actively searching for a specific tune to those who were looking for something else when they suddenly stumbled across “Ring of Fire” on a playlist and thought, “Oh, yeah, I remember that…”

But the key ingredient is a catalog that rewards repeated listens. As will become clear when we get to Jack Johnson and others like him, I don’t mean “reward” as some kind of aesthetic stamp of approval (although I do happen to love me my Johnny Cash). I’m using the word as objectively as I can, to denote a body of work that, for whatever reasons, encourages listeners to keep going beyond the track that initially piqued their interest, and then come back over and over again.

That’s the real key to success in a usage-based universe: it’s not about brief bursts of marketing-driven interest. It’s about the ability to keep people listening.

This pattern repeats across genres. Bach, Bob Marley, Eminem, Coldplay, Frank Sinatra, Van Morrison: all of them have staked out a particular slot in our charts below which they never fall. They’ll spike briefly when they have a new release or a baby or a sesquicentennial or something, but the really interesting thing is how well they do when there’s no particular reason.

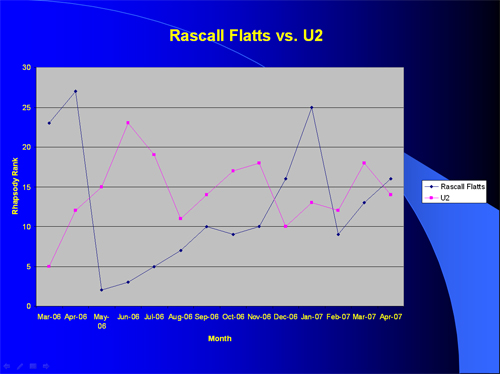

Still, I haven’t really gone out on a limb with any of the acts I’ve named so far, have I? Even if I tell you that New Country behemoths Rascall Flatts have spent the last 14 months growing to U2-sized proportions,

it still doesn’t sound like we’re talking about a radically different musical universe from the one we live in right now. Where’s the long tail we keep hearing about? When do we get to the good news for Yo La Tengo?

Patience. Like I said at the beginning, we have to wait a decade or so. But I submit that the hints we have right now are tantalizing nonetheless. That’s all these numbers are, by the way: hints. They don’t necessarily prove my point; they’re just odd shapes we see while looking through a telescope, trying to figure out what those creatures in the distance might be.

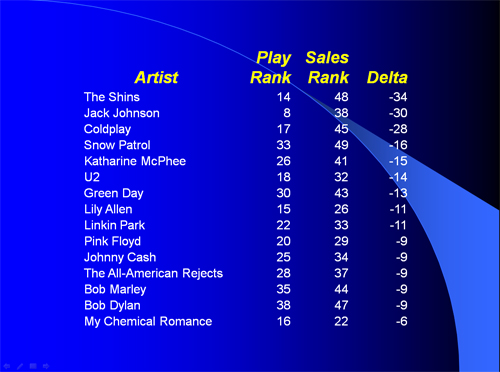

So, here’s another set of numbers we track monthly: we call it our delta chart. It’s a list of those artists in our top 50 whose play rank is significantly higher than their sales rank. Mind you, this doesn’t mean that nobody is buying their songs – it just means that even more people are listening to them over and over again.

This is our delta chart for March, and the Shins sit at the top because they had a new album that lots of people wanted to check out before deciding whether or not to buy it, but they’ll probably stay here for a few months, and that’s good news for both band and label – if you only appear on this chart for one month, it means lots of people heard about you, listened to you, and moved on to other things. But if you linger, it means you have Coldplay-sized legs.

Norah Jones, Modest Mouse, Death Cab for Cutie – these are some other acts who’ve spent extended periods on our delta chart. Quietly epic Brit-rockers Snow Patrol have been climbing this particular chart for six months. It’s been almost a year since their last record came out, so their sales rank has predictably decreased during that time. So has their play rank, for that matter – lots of new releases means lots of other tunes competing for people’s attention. But their plays have always outstripped their sales, and the plays continue at a high level even as the sales taper off. That indicates they’ve connected with an audience who keep coming back to them, and that’s good news for both the band and their current label, because they’re getting paid for every single play.

If I were Snow Patrol’s record company, I’d be buying each member his own car right now, as a gesture of my faith in their continued success.

Cuz look at the company they’re keeping: U2! Pink Floyd! Dylan! The delta chart isn’t designed to anoint new indie heroes, or to determine which new releases are likely to sell a zillion copies. It’s a way to see which artists are most likely to remain stuck in our collective heads a year from now. Arcade Fire will definitely be on April’s delta chart. How long they remain there will be a telling way to measure the impact of their second record.

Because you can have millions of plays without having millions of fans. Last century, this phenomenon was known as having a “turntable hit” – something DJs kept playing that never translated into an equal number of sales. Having a turntable hit used to be a pejorative. In the future, I believe it will be the goal.

Let’s dip below the level of artists who’ve achieved U2-levels of mass consciousness and see what patterns might emerge for them. Wilco’s a good example: a critically acclaimed band that can play several nights in a row at a venue like the Fillmore in San Francisco – they’re cool enough that their next record has already leaked on the internet, but it wasn’t in Rhapsody last month when I took a look at where they sat.

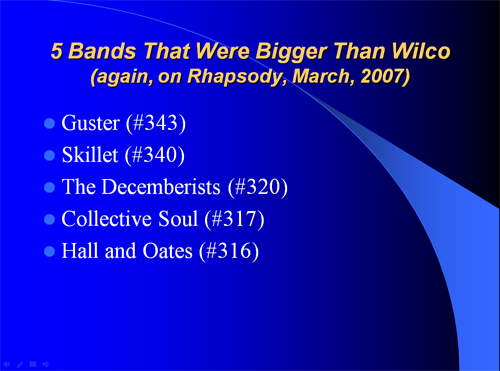

Wilco ranked #349 in total plays for the month. I picked out five acts in a few different genres who also hadn’t released anything new for a while, but whom I had kind of assumed were bigger than Wilco:

This list is a bit odd and, to be honest, it’s based on a month’s worth of stats that may vary wildly when we run the April numbers. But nothing prepared me for the idea that Jeff Tweedy is more AOR than Mark Knopfler, or that any Wilco song gets listened to more often than “Dock of the Bay.”

As it happens, no Wilco song gets played more than “Dock of the Bay,” which was our 1,049th most played track last month. Nothing by Wilco shows up in the top tracks list until “California Stars” at #3,702. So, they have fewer total listeners than Otis, but the fans they do have listen to more Wilco songs, more often, than the people who play Otis. Which means Wilco earned more royalties from us than Otis’ estate did, last month.

Have you digested that list? The next one’s much weirder:

The two most likely questions you have when looking at this chart are, “Really, Guster?” and, “Who the fuck are Skillet?”

The answer to the first question is yes, really, Guster are a lot bigger than you think. And the answer to the second one is, “Skillet are a hard-rocking Christian act with even more devoted fans than Wilco” – one measure of said fans’ devotion being the fact that they even have a dopey name for themselves: Panheads.

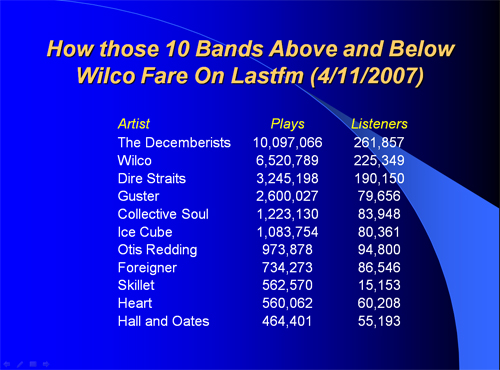

When I’m confronted with numbers like these, I try to check them with another source. Lastfm, a website that will log every single song you play on your computer and then let you know who else likes the same stuff you do, is another great place to analyze usage patterns. When I looked up Lastfm stats for those ten acts above and below Wilco in Rhapsody, they told a somewhat different story:

As in Rhapsody, Wilco gets played less on Lastfm than the Decemberists but more than Dire Straits and Otis Redding. However, neither Guster nor Skillet have as many fans registered there as the 225,000-plus Wilco listeners (Guster has about a quarter, and Skillet has less than a tenth), so Wilco beats them handily in total plays.

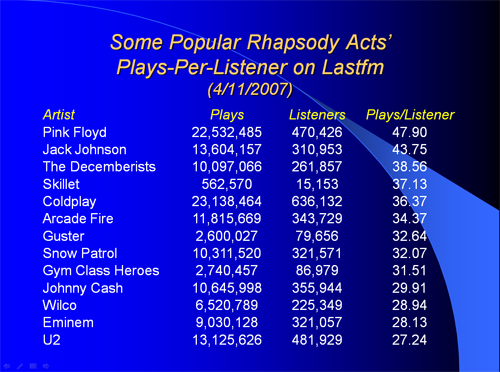

But look how the world gets inverted if you sort the chart by plays per listener:

Both Skillet and Guster fans listen to their group more often than Wilco’s. Does that matter? Absolutely, because this kind of math provides a decent indication of who stands to gain the most when you no longer get paid based on how many people know about you, but based on how much they like you.

And this is where things start looking up for cult acts like Yo La Tengo. When I say this is good news for them, I don’t necessarily mean it’s gonna make them rich, or even more popular. But I am saying the economics of adoration will shortly be paying more than psychic dividends.

The musical powerhouses of the 21st century will have plays-per-listener stats like these, but I should stress that I’m not suggesting every artist on this particular list is or will be a super-duper-star (I couldn’t cram everybody onto one slide, so you’ll just have to take my word that Insane Clown Posse and Iron Maiden sit above Pink Floyd by this particular metric). Plays-per-listener is just a great way to measure the engagement a given act has achieved with its audience, and engagement becomes increasingly important in a usage-based universe.

There’s a truism that everyone from corporate HR department heads to quantum physicists accepts: you get what you measure. I’m positive that measuring how often individuals choose to listen to something will favor a different kind of music than measuring how often someone else tries to get people to hear it, or succeeds in making them buy it.

I can’t pretend this different kind of music will automatically be better, but I will admit I think and hope so. As soon as the industry wakes up to the reality that they’ve stopped getting paid once, when someone buys the record, and are now being paid repeatedly, every time someone plays that record, longevity and fan devotion become assets the music business is compelled to seek out and actively nurture, rather than curiosities it regards with suspicion (you won’t find a lot of A&R guys saying they’re looking for the next Jimmy Buffet right now; but you will before too long). Better yet, the pre-existing Yo La Tengos of the world will be even more likely to say fuck off to those A&R guys, as they’ll already be in a position to reap their spoils directly.

But this shift doesn’t just mean you can make an easier living as a cult act. Niche artists suddenly have an opportunity to expand their audience beyond those who’ve already heard about them. Once it stops costing people money to listen to something new, and only costs them their time, they demonstrate a remarkable tendency to expand their musical horizons. We have more than 200,000 artists in Rhapsody, and almost 90% of them get played every month. A lot of those, of course, only get played once or twice, and that might just be by their moms. But the option is there, in a way it never has been before. And, as those first four numbers I projected attest, listeners aren’t just willing but decidedly eager to wander down thousands of different paths in search of something new to fall in love with.

Not all of those roads lead to an artistic utopia, of course. “Listenable over and over” does not automatically equal “brilliant” or even “deal-able.” If Rhapsody usage is an even vaguely accurate barometer, this particular brave new world seems to be filled with non-threatening, mid-tempo, guitar-based tunes by insistently uplifting troubadours.

So there is a dark side – I predict we’ll all be as sick of deep album artists in 2050 as we are of disposable pop r&b divas today (or, if you’re not sick of those divas today, that you will eventually be demonstrating your populist open mindedness by heatedly debating the merits of groovy acoustic jams, or proudly showing off your tickets to Snow Patrol’s fifth reunion tour).

Still, as someone who has always preferred what Mr. Christgau here once dubbed “semi-popular music,” I am a booster for the future. Not because I think the superstars of tomorrow will be significantly more palatable than the ones of today, but because I’m pretty sure they’ll be anointed by a completely different set of bishops.

And that’s the type of subtle but profound change I mentioned at the beginning that I’m most looking forward to, for the same reason I actually enjoy waking up a half hour sooner than I’d have to otherwise each morning in order to walk my dog before I go to work.

Most mornings Ruby and I turn left at the bottom of my driveway. Some mornings we turn right. I like to think these decisions are mine, but the truth is she pulls me one way far more often than I pull her the other, and I never really know when or why she’s going to stop and sniff something excitedly.

Most mornings Ruby and I turn left at the bottom of my driveway. Some mornings we turn right. I like to think these decisions are mine, but the truth is she pulls me one way far more often than I pull her the other, and I never really know when or why she’s going to stop and sniff something excitedly.

I take it for granted that the music business of the future will follow the money, and music critics will follow the business even while they pretend to be explaining why the audience likes what it does.

But the audience will be doing the tugging way more forcefully than either contingent is used to. And those of us whose jobs are based on understanding what the audience responds to are going to find ourselves sticking our collective nose in some fucking weird bushes we’d never really noticed before.