While  the amazing storage capacity mp3 players made possible at the turn of this century felt pretty profound, the Walkman was a more revolutionary consumer electronic device, as this presentation from the 2010 Pop Conference attempts to explain. I searched in vain when writing this for a Malcolm McLaren quote I remembered from the late-’70s/early-’80s, in which he damningly contrasted white people hiding behind Walkman headphones with black youth who more proudly imposed their soundtracks on the world around them. Like a lot of things McLaren said, it was savvy, provocative, and wrong. Turns out those headphones had more power to shape the environment.

the amazing storage capacity mp3 players made possible at the turn of this century felt pretty profound, the Walkman was a more revolutionary consumer electronic device, as this presentation from the 2010 Pop Conference attempts to explain. I searched in vain when writing this for a Malcolm McLaren quote I remembered from the late-’70s/early-’80s, in which he damningly contrasted white people hiding behind Walkman headphones with black youth who more proudly imposed their soundtracks on the world around them. Like a lot of things McLaren said, it was savvy, provocative, and wrong. Turns out those headphones had more power to shape the environment.

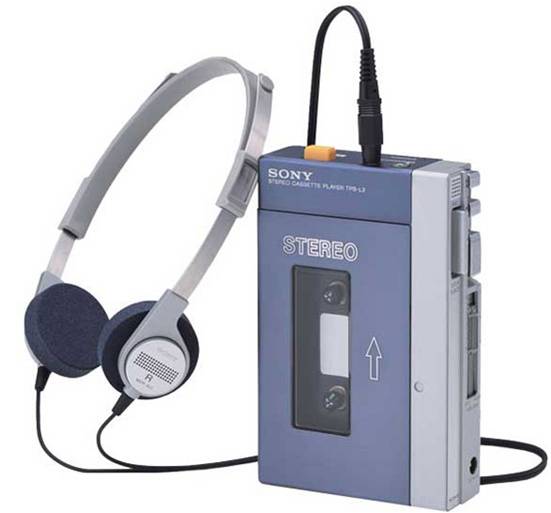

The world changed, quietly, on June 22nd 1979, the day Sony unveiled the first “personal stereo” to skeptical journalists in Tokyo .

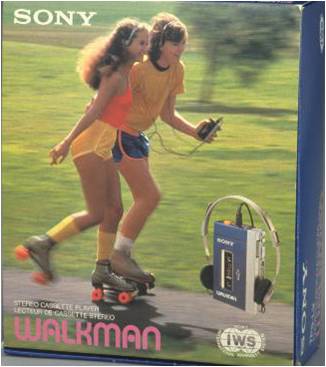

The device, originally marketed as a Soundabout in the U.S., a Stowaway in the U.K., and a Freestyle in Sweden, soon became known worldwide (and was eventually immortalized in the Oxford English Dictionary) as a Walkman.

This contraption began changing the music business almost immediately, though some people caught on sooner than others. Bow Wow Wow were singing “C30 C60 C90 Go!” (an ode to the joys of taping music off the radio) in 1980; Chris Blackwell of Island records announced the “one plus one” format in which new releases including U2’s October came out on one side of a cassette while the other side was blank and recordable in 1981; Time magazine hailed the Walkman as “gadget of the year” in 1982; and pre-recorded cassette sales had surpassed sales of vinyl LPs by 1983.

The recording industry, presented with all this evidence of a shift in the cultural zeitgeist that had more people listening to more music in more places than ever before, responded thusly in 1984:

It’s funny because it’s sad. And also because it’s typical. We’ve watched a similar cycle play out with mp3s and the iPod this decade. In each case a new format for recorded music interacted with an ingeniously designed and marketed portable device to produce an explosion of listening. In each case the format and devices that made use of it had existed for years before this particular combination of the two made the cover of Time magazine. And in each case the recording industry tried to exploit the phenomenon while completely misunderstanding what was driving it.

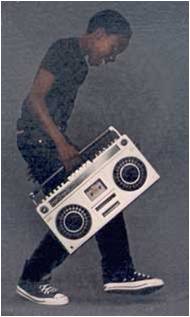

The Walkman, like the iPod after it, actually did pose a serious challenge to the recording industry’s established business, but not because it gave people the ability to hear music they hadn’t paid for. In fact, unlike boomboxes,

which exploded in popularity contemporaneously with the Walkman and helped fuel the 1980s’ demand for cassettes over LPs, the Walkman was notable for what it lacked: a record button.

The Walkman offered listeners something far more powerful than free music. It gave them control: control of what was heard; control of when it was heard; control of where it was heard; control, ultimately, of the listener’s environment. Consciously or not, that’s what the record industry was really fighting in 1984, and what they’re fighting even more fiercely today. Not loss of revenue. Loss of control.

Because once the speakers disappear, you never know for sure what someone’s listening to.

We’ll take a look at the consequences of such unpredictability shortly. But first we’re going to rewind to 1978 to see how Sony’s engineers were thinking about what they did, since even they didn’t realize what they were unleashing. Then we’ll fast forward to today, and take a look at what they unwittingly wrought.

This is the Walkman’s dad, the TC-D5, a high-quality portable cassette recorder launched in 1978.

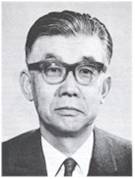

Or maybe it’s the Walkman’s mom, because I suppose this is the Walkman’s dad:

That’s Masaru Ibuka, one of Sony’s co-founders. There are different stories about whose idea the Walkman was, but the most prevalent is also my favorite.

Supposedly, Ibuka loved listening to classical music on the TC-D5 during long plane rides. The audio quality was excellent, but the device was heavy and difficult to power, so he asked Sony’s engineers to come up with something smaller and more convenient.

They did so, by adapting another high quality recorder, the TCM-600, also known as the Pressman.

In 1978, this was the smallest tape recorder in the world that used standard cassettes, but it was a costly device whose focus was on monaural recording – it was mostly used by reporters and others who needed a small dictating machine.

It’s hard to say whether the most important differences between the Pressman and the Walkman are internal, or conceptual.

The one on the left was expensive, had a record function, and played back in mono. The one on the right was significantly cheaper, had no record function or speaker, but offered stereo sound via headphones.

The lack of a recording option was a big deal. On one hand, removing that machinery made room for all the components that enabled stereo playback, while also dramatically reducing the cost. On the other hand, very few people at Sony, and almost nobody else in the world, thought there was a market for a cassette player that couldn’t record anything. Who, beyond the well-paid, frequent-flying co-founder of Sony might actually use such a thing?

Well, Sony’s CEO, Akio Morita, for one. He had borrowed the prototype from Ibuka and taken it on a golf outing with some friends, who all enjoyed it. Morita may qualify as a visionary for pushing his team to mass produce this odd device, insisting as he reportedly did that it would be a hit if they could just keep the price affordable for young people.

But there were some things Morita couldn’t foresee. He’s also responsible for that silly orange button and the fact that the first model had two headphone jacks – he thought it would be rude for one person to listen to music alone, and insisted engineers add that orange “hotline” button; pressing it reduced the playback volume and allowed you to talk to your friend without either of you having to remove your headphones.

Morita was very right about how successful a truly portable music player would prove, and very wrong about how its purchasers would ultimately use it. It’s hard to remember now, but listening to music privately while in public was difficult to conceive of in 1979.

Something like the Walkman had in fact been invented in 1972. Andreas Pavel had been pitching what he called the “Stereobelt” to multiple electronics companies for seven years, but everyone rejected the idea. “They all said they didn’t think people would be so crazy as to run around with headphones,” he recalled to the New York Times. “This is just a gadget, a useless gadget of a crazy nut.”

Sony’s initial ads and packaging betray this mental block, as they mostly featured pairs of active young people sharing a device, often while on rollerskates.

Young people did indeed buy lots of Walkmen, and some of them probably even took it roller skating. But all kinds of people bought the device, and most of them used it to listen to music alone.

The rewards for fulfilling a need nobody previously realized they had can be great. Sony sold 50 million Walkmen in the first ten years, while Toshiba, Panasonic, Aiwa and others did equally well with knock-offs.

One mark of just how ground-breaking the device proved is the cottage industry that sprang up among sociologists and other cultural critics analyzing what this new mode of listening might herald for society.

Shuhei Hosokawa, who coined the term “The Walkman Effect” in 1984, began that article by citing a French journalist interviewing young adults about Walkman use. His questions included,

- “Are men who use the Walkman human or not?”

- “Are they psychotic or schizophrenic?”

- “Are you worried about the fate of humanity?”

That journalist had plenty of company. Alan Bloom, in The Closing of the American Mind, derided the Walkman as downright masturbatory, and carped that the device made young people incapable of appreciating Great Works:

“As long as they have the Walkman on, they cannot hear what the great tradition has to say. And, after its prolonged use, when they take it off, they find they are deaf.”

In Christianity Today, Mark Noll described the Walkman in near-Satanic terms as

“One more competitor to the voice of God.”

Twenty years later, Norman Lebrecht was still railing against the device, insisting that,

“Beyond hearing loss, the Walkman attacked our musical taste. Instead of seeking melody, listeners grew satisfied with crump crump rhythm. The decline in classical concertgoing may be partly ascribed to the Walkman, which devalued magnificence and rendered it utilitarian…It promoted autism and isolation, with consequences yet untold.”

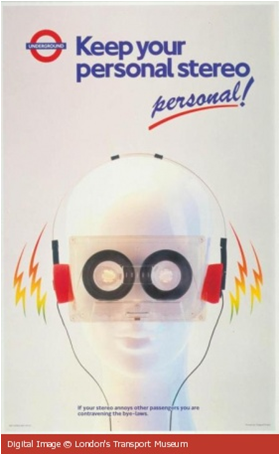

“Autism” is a word that comes up a lot in critiques of the Walkman; the ability it gave an individual to separate himself from his fellow man drove a lot of the outcry, even when that ability wasn’t directly referenced. A good example can be found in campaigns such as this one:

In the ‘90s, the London Underground made it a crime to play your Walkman too loudly – as Beautiful South fan Andrew Dunn learned in 1994 when he refused to turn down his volume after a fellow tube rider complained. Dunn wound up owing a L200 fine and L100 in court costs.

As a guy who’s often being asked by flight attendants to turn down the volume of my own portable device, I can sympathize with Mr. Dunn, who implied to the NME that he was being persecuted for something other than noise.

I have to ask: when you’re on an airplane with turbo engines rumbling at 140 decibels, babies shrieking, two dudes in front of you droning on and on about how totally drunk their buddy was last night, and two people behind you sharing stories of how Jesus touched their lives, what makes the tinny buzzing of guitars leaking out of a pair of headphones the thing people feel justified in silencing?

Rey Chow hints why when she argues that, in collectivist states like China, Walkman usage can be a subversive form of sabotage, allowing Chinese youth to be

“deaf to the loudspeakers of history.” She believes that, “the autism of the Walkman listener irritates onlookers precisely because the onlookers find themselves reduced to the activity of looking alone. For once, voyeurism yields no secrets.”

Vincent Jackson, in a 1994 article about the glares he got on the London Underground whenever he put on his Walkman, echoes Chow:

“It’s not the sound coming out of your headphones that bothers people around you. It’s the symbolism.”

He tested his theory by riding the tube wearing his device but without playing any music at all through it, and cataloged all the same angry reactions he got as when he pumped up the volume.

Overheated or not, overjoyed or merely annoyed by the Walkman as they might be, these critics all share a belief that the device has profound power, and all their arguments circle around the same assumption: whatever the Walkman wearer might be listening to, it represents a threat to those in charge.

I repeat: it’s all about control. Transistor radios

let you bring music wherever you went, but gave you no say in what you heard. Boomboxes

gave you a say, as well as the illusion that YOU could be the broadcaster, at least in a small radius around you. But the Walkman

with its little foamy headphones was more revolutionary, and not only because it was easier to carry around.

The Walkman was private. It gave people a new way to listen to music, which changed their relationship to it. Music became a bigger part of their lives, and their expectations about where they could hear it and what should be playing when they did shifted dramatically.

Cassette technology eventually gave way to digital audio, but the Walkman’s two main innovations – private listening in public places coupled with listener control over what plays – live on.

Listener control has in fact expanded exponentially: the cheap mass storage of the iPod means anyone who can afford one can walk around with 50,000 songs in her pocket today, and the combination of mobile apps and cloud-based services mean she’ll be able to access millions of songs from her handset tomorrow.

This is different in scale but not in kind from the summer of 1983, which I spent transferring most of my 500 LP collection to 200 Maxell XL II-S cassettes before moving across country to attend college. I couldn’t bring the LPs with me, but I couldn’t leave all that music behind, either, and thanks to technology I no longer had to.

It was a great summer, even if I found myself stressing about which records made the cut and which would remain unrecorded, and then had to make another series of Sophie’s Choices about which cassettes would join me in my carry-on to be played in flight on my Walkman, and which would have to be checked with the rest of my luggage.

Quandaries like those now seem quaint. Record industry disquiet, on the other hand, is as familiar as ever – and is a big reason we all say “iPod” instead of “Walkman” when we talk about MP3 players.

There’s no reason Sony shouldn’t have dominated MP3 players from the beginning. But the Walkman’s success cemented a strategy Sony had been contemplating for years: acquiring content companies to complement their hardware business. Their acquisition of CBS records in 1988 is arguably the moment they ceded meaningful personal stereo innovation to others.

They wanted synergy, but they got internecine warfare. In the U.S., the Recording Industry Association of America, of which Sony Music was now a big part, had been insisting for years that blank cassette sales represented significant lost revenue for the music industry (in typical over-reaching fashion, the figure they bandied about was a billion dollars a year). If they’d had their way, the ungodly amount of money I’d paid for all those Maxell cassettes would have been even ungodlier, and labels would have pocketed the difference.

In 1992, they finally got their way, with something called the Audio Home Recording Act, which mandated a 3% tax on all blank digital music media and recorders, which was then distributed to labels, publishers and songwriters. In theory, consumers got something in return: an acknowledgement by copyright owners that home taping does not constitute copyright infringement.

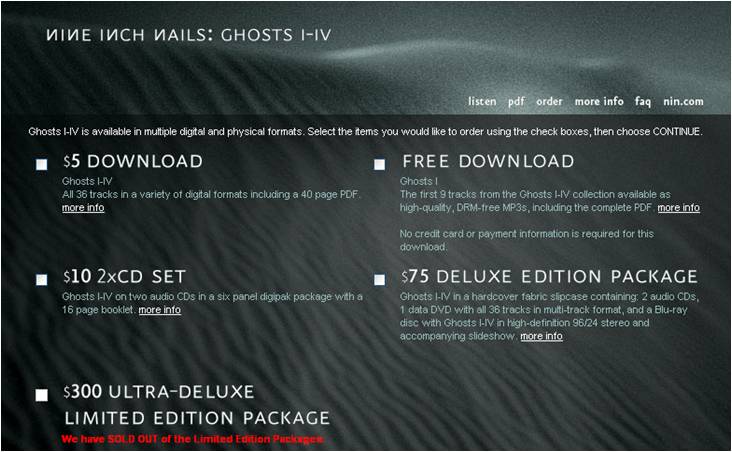

But the act led to weirdness like this:

The only difference between the two is price. The “music” CD-R costs more, even though the same silver discs lie inside each package.

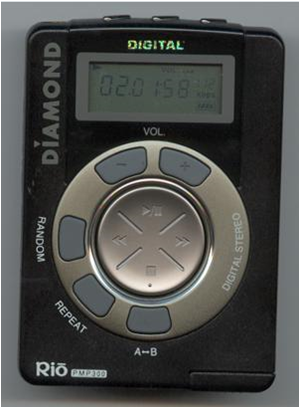

The Audio Home Recording Act was part of a larger pre-emptive effort the RIAA was fighting against digital audio. In 1998, the RIAA got a temporary restraining order against one of the first portable MP3 players, the Diamond Rio, by claiming the device violated the act.

They eventually lost the lawsuit, but their position was clear: such devices were a threat to their business. Keep in mind that most MP3 players, like the Walkman before them, HAD NO RECORD FUNCTION.

That didn’t matter. What mattered was the assumption that the devices primarily relied on media the labels didn’t sell you.

The labels could have been selling MP3s in the ‘90s, of course. By the end of the decade, MP3 had surpassed the word “sex” as Yahoo’s most searched for term. The market hadn’t just spoken, it had had a screaming orgasm, but major labels would still wait ten years before making their catalogs available for sale in the format. It was 1983 all over again,

with labels responding to an explosion of more people listening to more music than ever before by treating a new consumer demand as a crime, rather than an opportunity.

To be sure, the ease of procuring MP3s for free was a massive part of what drove their popularity. But the ability to hear just about anything you want, just about anywhere you might be is ultimately a bigger deal. Anybody interested in helping musicians make a living making music needs focus on how those phenomena are changing what we listen to, and adapt their business accordingly.

This isn’t pie-in-the-sky, anarchistic label bashing, by the way. Just this week the Government Accountability Office released the results of a year-long study of the effects of piracy on the U.S. economy. Among their conclusions:

- There must be some damage from piracy

- However, there’s no real way to quantify it

- It’s probably smaller than IP businesses insist

- There are instances in which piracy can benefit consumers, businesses, and society

(There’s actually a whole section of the report headed, “Certain Stakeholders May Experience Positive Economic Effects of Counterfeiting and Piracy”).

File trading may well result in lost money for copyright owners (that GAO report cites a study that suggests one in every five P2P downloads might represent a lost sale), but a funny thing happens when you make the entire history of recorded music available for free, and then give people an easy way to walk around with that library in their pockets. You get unprecedented insights into which bits of your catalog actually engage them. And one of the things you learn is that, even when people have free access to every last song your biggest stars have ever recorded, those people don’t necessarily bother to take them.

The implications of that are fairly profound, and go well beyond clichés about the death of the album and the return of singles. The days of locking a song people want inside a bundle of tracks that costs $15 or more are indeed fading fast, but labels are getting something potentially more valuable in return. As they relinquish control to listeners, they gain unprecedented knowledge about what those listeners return to over and over again. They can finally hear exactly what those headphones have been hiding for the last thirty years.

A company called Big Champagne analyzes what gets traded on P2P networks, which of those songs linger in listener’s libraries, and how those two correlate (or fail to) with what’s being broadcast on radio or sold via online services. One of their most revealing metrics is Tracks Per Fan – a count of how many songs the average fan of a particular artist has in her library.

Most listeners, it seems, don’t even carry around an entire album by the world’s most popular artists. For the 500 artists with the most tracks in the libraries of several million listeners, the average TPF is 3.27.

Even the artists with higher-than-average TPFs don’t exactly stun you with their numbers:

| TPF Rank | Artist | TPF |

| 1 | Lil Wayne | 17.26 |

| 2 | Gucci Mane | 8.44 |

| 3 | Aventura | 8.24 |

| 4 | The Beatles | 8.22 |

| 5 | Eminem | 7.66 |

| 6 | Michael Jackson | 7.59 |

| 7 | 2Pac | 7.27 |

| 8 | Wisin & Yandel | 7.26 |

| 9 | Metallica | 6.87 |

| 10 | Jack Johnson | 6.72 |

| 11 | Jay-Z | 6.4 |

| 12 | Dave Matthews | 6.39 |

| 13 | George Strait | 6.3 |

| 14 | Tech N9ne | 6.2 |

| 15 | blink-182 | 6.17 |

| 16 | Taylor Swift | 6.02 |

| 17 | Led Zeppelin | 5.95 |

| 18 | Trey Songz | 5.92 |

| 19 | Usher | 5.87 |

| 20 | R. Kelly | 5.85 |

| 21 | Lil Boosie | 5.82 |

| 22 | PLIES | 5.82 |

| 23 | Beyonce Knowles | 5.73 |

| 24 | Kirk Franklin | 5.7 |

| 25 | DRAKE | 5.7 |

What are we to make of a list like this (beyond the fact that Lil Wayne demolishes everyone else, I mean)? One thing that jumps out at me is the ratio of new to old: it’s about a 60/40 split of currently charting vs. catalog artists. Another thing worth noting is the range of styles: there’s Hip-Hop, Reggaeton, Bachata, R&B, Country, Metal, Classic Rock, Alternative and Jam Rock, just in the top 25.

You see a similar range, and some more surprises, at the other end of that top 500 list.

| Rank | Artist | TPF |

| 476 | Yes | 1.48 |

| 477 | O.C. | 1.47 |

| 478 | Dorrough | 1.45 |

| 479 | Kevin Rudolf | 1.45 |

| 480 | Swizz Beatz | 1.43 |

| 481 | Huey | 1.41 |

| 482 | Dorrough Music | 1.41 |

| 483 | Air (French Band) | 1.4 |

| 484 | Travis | 1.4 |

| 485 | Man | 1.38 |

| 486 | P.L. | 1.37 |

| 487 | Asia | 1.37 |

| 488 | The Time | 1.36 |

| 489 | Estelle | 1.36 |

| 490 | Kardinal Offishall | 1.32 |

| 491 | DOLLA | 1.32 |

| 492 | Sweet | 1.3 |

| 493 | Down | 1.29 |

| 494 | Cupid | 1.29 |

| 495 | Savage | 1.27 |

| 496 | IYAZ | 1.26 |

| 497 | ORIANTHI | 1.25 |

| 498 | S.O.S. Band | 1.25 |

| 499 | ROSCOE DASH | 1.24 |

| 500 | V.I.C. | 1.22 |

I have a low opinion of humanity, so I am not overly bothered that Yes and Asia are two of the top acts on people’s iPods. But I will admit that Sweet and the Time are pleasant surprises.

For Sweet, that 1.30 figure implies lots of people have “Ballroom Blitz,” and a smaller percentage of that group also has “Little Willy.” Maybe this is not so surprising after all. “Little Willy” is a fine fucking song, and it stands to reason that it should live on.

What’s amazing is that it now has a way to, a way that transcends radio formats, demographics, greatest hits packages, or clever use in movie soundtracks. It’s just floating out there, like some odd strand of DNA. And it’s thriving.

I submit that this is a good thing for the music business. Many of these artists and their 1.3 or 6.2 or 8.4 songs are being actively marketed. Almost as many of them are not. Hidden in stats like these are formulas for identifying more of the latter, and wasting less money on the former.

Keep in mind that TPF is an average. So, while Bob Dylan has 3.64 tracks per fan, that means some folks have dozens of Dylan songs and some have only one. To put it in mildly embarrassing perspective: I have 423 Dylan tunes on my iPod, which means for every geek like me there have to be 159 people who only have “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” (I originally typed “Like a Rolling Stone,” by the way, but the stats say “Knockin” is in fact the most widely shared Dylan tune).

That spread of 159 normal people for every 1 completist hoarder suggests labels aren’t losing nearly as much as they claim. Or, rather, if they are it’s not because people are stealing songs they’d have purchased otherwise. It’s because people are no longer paying for songs they never wanted in the first place.

Let’s say the GAO is right and 1 of every 5 mp3s making up these figures represents a lost dollar (or, if you want to be generous, a lost sale of whatever album contained the tune someone really wanted). That still means 80% of this music is being listened to by people who wouldn’t have engaged with it before. That’s an amazing trade.

The music business of the past believed getting people who wanted 1 or 2 songs to pay for 10 was the natural order of things. The music business of the future accepts the ratio of 159 casual listeners for every 1 fanatic, and does what it can, on an artist by artist basis, to move people from the low end of the spectrum to the high, but it doesn’t insist they all start in the middle.

Here’s why this makes sense: if low TPFs imply a somewhat impatient or even A.D.D. afflicted audience, they also indicate a more curious, questing one than the business traditionally assumed, an audience that jumps back and forward in time, keeping old songs alive indefinitely and spreading new ones in a wide variety of genres rapidly.

The range of styles and eras on those lists don’t indicate multiple, closed-off, niche audiences. As access becomes easier and storage cheaper, people start listening to a little bit of everything, as demonstrated by another Big Champagne metric.

“Artist correlation” basically tells you what percentage of fans who have one artist in their collection also have another. A lot of those correlations are what you might expect (81% of Katy Perry fans also listen to Lady Gaga, for instance), but some of them are counterintuitive:

Guns N’ Roses Artist Correlation

| Artist | By | Reverse |

| Eminem | 67.04% | 21.51% |

| Black Eyed Peas | 58.89% | 21.99% |

| Nickelback | 55.58% | 32.28% |

| Linkin Park | 50.85% | 30.78% |

| AC/DC | 48.90% | 50.18% |

| Metallica | 48.52% | 45.98% |

| Bon Jovi | 47.68% | 45.49% |

| Kid Rock | 45.11% | 40.00% |

| Green Day | 44.36% | 33.12% |

| 3 Doors Down | 42.20% | 36.07% |

| Queen | 41.99% | 40.34% |

| Tim McGraw | 38.97% | 32.06% |

| The Beatles | 38.69% | 36.26% |

| The Red Hot Chili Peppers | 37.35% | 40.05% |

| Kenny Chesney | 37.07% | 33.67% |

| The Eagles | 35.99% | 45.89% |

| Led Zeppelin | 34.20% | 48.79% |

| Garth Brooks | 33.84% | 38.40% |

| The Rolling Stones | 32.63% | 46.59% |

| Def Leppard | 31.21% | 53.62% |

Almost 40% of Guns N’ Roses fans also listen to Tim McGraw. Nearly as many listen to Kenny Chesney or Garth Brooks. How many radio stations play all four?

Some other random examples from similar charts: about 38% of Beck fans listen to Johnny Cash and Eric Clapton. 73% of people with R.E.M. on their device also have at least one T.I. track, and 27% have some Phil Collins, while 31% of Barry Manilow fans and 30% of Neil Diamond fans dig R.E.M..

As Eric Garland, Big Champagne’s C.E.O. and the guy who provided me with all these charts, likes to say, “People are not radio formats.”

They probably never were, but it took the Walkman and blank cassettes to let the average bus rider be his own DJ, and it took the iPod and MP3s to give him a big enough library to build some seriously idiosyncratic playlists.

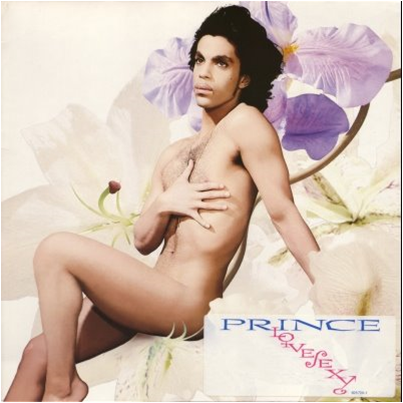

Labels aren’t the only ones uncomfortable with these changes. In 1988, Prince had the CD version of Lovesexy mastered as a single track. It was his rebellion against the then-new phenomenon of shuffle play. He’d made an album, dammit, and that’s the way he wanted you to hear it.

Part of me admires strongly-held artistic visions. Another part of me says, “Fuck you, fascist.”

And yet another part of me giggles at what happened when the album first went live on digital download sites: since it was delivered as a single track, you could buy it for 99 cents.

There are a bunch of morals packed inside that sequence of events, but I’ll limit myself to one: there’s what the audience wants, and what you want them to want.

Sometimes it’s worth getting that balance wrong, and losing money as a result.

But sometimes it’s just stubborn and stupid.