Presented  at the 2009 Pop Conference, and later published as a chapbook which you can purchase for 99 cents from Feedback Press, or from Amazon if you prefer an electronic edition. I have no humorous anecdotes about this one, as they are all contained within the paper itself. But I should probably explain that it’s broken up into pretentiously-titled sections, including an overture and a coda, because that seemed like the best way of honoring an album that is so lovably, ridiculously overwrought. If it’s not clear from everything that follows, I still adore this record. There’s a lot to admire in being ridiculous and overwrought.

at the 2009 Pop Conference, and later published as a chapbook which you can purchase for 99 cents from Feedback Press, or from Amazon if you prefer an electronic edition. I have no humorous anecdotes about this one, as they are all contained within the paper itself. But I should probably explain that it’s broken up into pretentiously-titled sections, including an overture and a coda, because that seemed like the best way of honoring an album that is so lovably, ridiculously overwrought. If it’s not clear from everything that follows, I still adore this record. There’s a lot to admire in being ridiculous and overwrought.

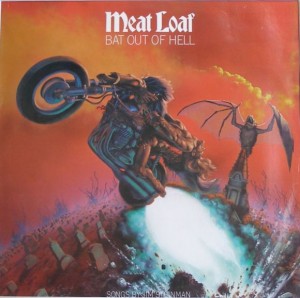

Overture: The Cover

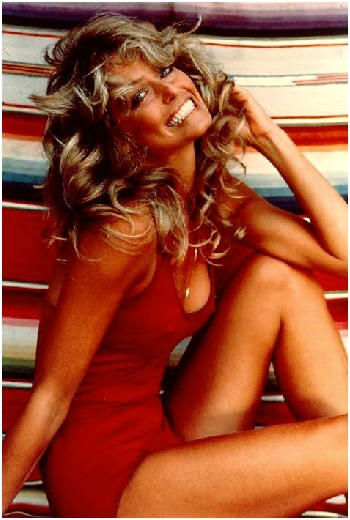

It’s 1977, bleeding into 1978. I am 12 years old. This is on my wall,

this is carefully hidden in my closet,

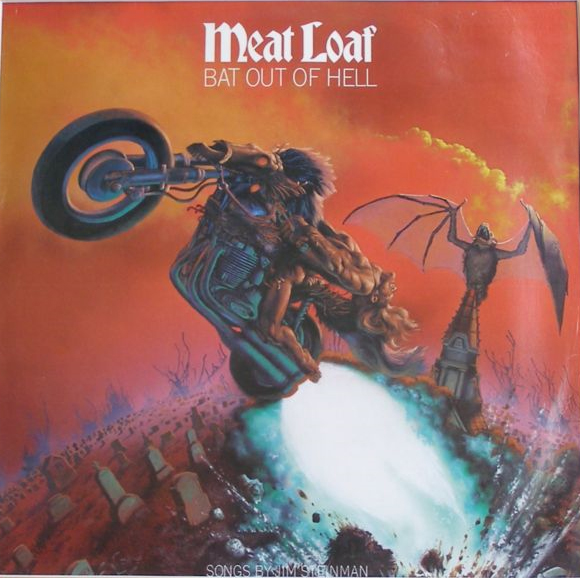

and this is in my hands

Any discussion of Bat Out of Hell has to begin with this image. The others are optional, but I believe some version of each is integral to the experience, and we will be returning to mine before too long.

But we start here, because some books really can be judged by their cover. This tells you almost everything you need to know about the record: there will be sex, death and motorcycles; it will all be overwrought; and at least one actual bat will make an appearance.

I knew this cover was powerful the day I got the record, because my grandmother, who bought it for me at the local Korvettes, complained about it all the way to the cash register. Importantly, she didn’t refuse to buy it – she just asked me to explain the picture, which I couldn’t, beyond saying it was awesome. And since she couldn’t articulate why it bothered her, even though it looked like it should, I got it.

Years passed before I noticed the other important thing about this album cover: Jim Steinman, the composer, gets his own credit. By the time this got re-issued on CD, his name would be almost as big as the singer’s, but here on my thirty-two year old LP it’s at the bottom, obscured by the motorcycle’s orgasm.

The motorcycle might be coming, but the entire cover is a picture of its own, larger orgasm. Please note the rider’s ecstatic position, and also his lack of clothes.

So, we’ve got orgasms within orgasms, and we haven’t even dropped the needle on the vinyl yet. As it happens, that’s a reasonably apt description of the music we’ll hear once we do.

We’re not there, yet, though. Because this paper is more about what the music thinks than how it sounds, and it turns out this cover is no accident. It’s important enough to the music it encloses that songwriter Jim Steinman gets a credit for “cover concept” in the liner notes above the illustrator, Richard Corben. Yet Corben wasn’t just a hired hand – he was an artist Steinman fought for. “They were going to use the guy who does the KISS stuff,” he told an interviewer at the time. “But I hated it. Like all the KISS covers, the stuff he came up with was cheap and tacky.”

Laugh with my adult self about the Bat Out of Hell cover, then, but recognize it wasn’t a joke to me in 1977, and it’s still not one to Steinman, who considers the illustrator a kindred soul: “In Corben’s worlds,” he says on his website, “the ‘acoustic’ has been banished – everything is gloriously amplified…the sexual richness is overwhelming – this is a world that is endlessly horny for wonder and magic.”

Last thing to note before the needle drops: the motorcycle is not on an actual road. This is more important than it looks, right now, but, like the Farrah poster, it’s going to take me a little while to explain why.

Part the First: Hell

OK, now we’re listening to the first song, also called “Bat Out of Hell.” It’s almost ten minutes long, but the song itself doesn’t really start till almost two minutes in. The first minute fifty is an overture of sorts, a statement of purpose. It’s a smorgasbord of parts, with everybody in the band playing as fast and as loud and as complexly as producer Todd Rundgren will let them.

For all its apparent bombast, Bat’s ingredients are as simple as can be. Meat Loaf insisted it “was written as a backlash to people like Frampton. It comes from the same roots as punk rock.” And Steinman, who claims he was equally inspired by Wagner and Little Richard, saw it as an attempt to recapture the magic of the 1960s, which he called, “a decade of rock and roll…everyone got older and left rock behind them. We all live too comfortably. That’s why we like FM radio.”

Steinman’s stated goal with this particular tune was “to write the most extreme car crash song of all time,” and while there’s something perverse about a long-haired wunderkind writing a multi-part, 10-minute epic as a fuck you to the sins of FM radio, I’m convinced such contradictions explain the album’s success. Like most great rock and roll, Bat is petty obviously about wanting to fuck something. But its real genius lies in the way it channels the desire of those who never have, and fear they never will. Bat’s many ostentatious filigrees are just a loincloth over its throbbing hard cock, a charmingly inept attempt to make its subject matter sound more sophisticated.

When the album came out, Sylvie Simmons described the music as “Springsteen-plus,” which makes sense, since that’s Roy Bittan and Max Weinberg from the E Street band pounding the piano and drums. Lyrically, though, it’s Springsteen-minus, as Steinman himself explained to Sounds magazine in 1978: “They try to compare me to Springsteen, but he mentions Harlem and names of streets and things in his songs.”

Steinman would never bog down one of his creations with anything so mundane. As the cover he conceived suggests, Bat’s not about your dreams – it is the dream. And like any dream that feels powerful and dangerous while you’re having it, it starts to crumble and sound silly as soon as you try describing it to someone else.

But I’m going to make the attempt anyway…

[dciframe]http://cdn.topspin.net/api/v3/player/195953,200,30,0,auto,border:0px solid blue;align:left;[/dciframe]

The bat who’s racing out of hell in this song is a guy, who’s just told his baby that she’s the only thing in this whole world that’s pure and good and right, but he must leave her before the final crack of dawn, which is an odd phrase, since it suggests there’s more than one crack of dawn, or maybe that it’s a sound – whatever, it’s another example of trying to make things sound grander than they really are.

The singer might be a vampire, or he could be a biker who just knifed someone and has to run before the cops arrive. But I’m pretty sure he’s just a kid who hates this town, where nothing really rocks and nothing really rolls. And I’m also pretty sure that kid has neither a driver’s license nor a motorcycle. Here’s why:

[dciframe]http://cdn.topspin.net/api/v3/player/195955,200,30,0,auto,border:0px solid blue;align:left;[/dciframe]

Did you notice how he sang about riding “faster than any other boy has ever gone”? That sounds more like a daydreaming kid than a reminiscing man, no? Turns out the word isn’t exactly a Freudian slip – “Bat” was one of three songs on the album that began life in a musical theater piece Steinman wrote called Neverland and based, as the title suggests, on Peter Pan. “It’s about chemically mutated teenagers who can never grow up,” he told Rolling Stone at the time, “lost boys living in an antiseptic village who have never before seen a girl.”

Remember that, because the notion of girls as alien beings will keep recurring, and adds an extra frisson to another odd note, the line: “My skin is raw but my soul is ripe.” If the musical arrangement’s self-indulgence is part of its appeal, that lyric suggests the song is masturbatory in every sense of the word.

Finally, there are those strange perspective shifts just before and after the motorcycle plunges off the cliff: “I never see the sudden curve until it’s way too late,” followed by “Then I’m dying at the bottom of a pit in the blazing sun.” Most teenage death songs are sung by the weeping, surviving lover, but this one remains in the first person even as the accident flings our narrator’s still-beating heart out of his body. The story isn’t being narrated from beyond the grave, but it’s not exactly in the present tense, either. Let’s call it the omnipresent tense, since this whole thing is a fantasy our boy keeps having over and over again.

Steinman considered Fantasy one of six essential ingredients in all good rock and roll. The others, which he recited to interviewer after interviewer throughout ‘78, were Fever, Romance, Violence, Rebellion and Fun.

The thing about pre-pubescent boys, though, is that they have odd ideas about what’s fun.

Part the Second: Jokes?

The entire album is so exaggerated it’s funny. The title track, for instance, doesn’t end as the narrator watches his heart fly out of his body – it leaves enough time for him to note that it’s flying away like a bat out of hell.

There are a lot of jokes in Bat, many of them intentional. They’re all vaguely creepy, in that you want to laugh but can’t quite tell if you’re supposed to. Eve Zibart, reviewing a Meat Loaf performance in 1978 for the Washington Post, declared Steinman, “A parodist so accomplished that the result is taken at face value by most of his audience,” then added, “There is the possibility that all this isn’t meant to be funny. But I don’t believe it.”

That’s a reasonable response to the work, if you’re a well-adjusted, sexually-satisfied adult. Bat wasn’t created by or for such people, as both the back cover and the intro to the second song demonstrate.

Now, Steinman spent a good deal of ‘78 insisting to interviewers that Bat had a sense of humor, and expressing his continual amazement “at how ineptly some people – rock critics in particular – are able to deal with humor.” But as punch lines go, that one’s pretty lame.

Because the gag doesn’t really function as a knowing wink, a signal from the composer to the listener that what preceded it was a necessary set-up. It feels more like an unknowing wink, the kind of clunker an awkward kid blurts out in a misguided effort to seem worldly, or to cover himself after revealing too much.

The same thing applies to the song it introduces, “You Took The Words Right Out of My Mouth.” Like many of the titles on the album, it’s a cliché. When Steinman wasn’t busy defending his arrangements or insisting he got the joke to interviewers, he was explaining that he knew his titles were clichés, but that was the point: “I love listening to a cliché,” he’d say, “You take it and break it down like a chemical substance.”

He does exactly that on this song, in which our boy swears he was about to say “I love you,” but the girl took the words right out of his mouth. She doesn’t do this metaphorically, by saying it before he can, but literally, with her tongue, inserting it into his mouth and removing his ability to say anything.

Disturbingly, this leads to a lasting condition for the boy, because three songs later he’s just as literal-minded, but even more cold-hearted

[dciframe]http://cdn.topspin.net/api/v3/player/195958,200,30,0,auto,border:0px solid blue;align:left;[/dciframe]

He wants her (one), he needs her (two). But she can’t have the third thing, his love.

It’s kind of clever, but kind-of-clever is how you describe the kid who’s never gonna get laid. And that kid’s claim to be dissecting clichés rings a little hollow. Because clichés might be fun to analyze, but they’re also received wisdom – what you turn to when you lack the experience to provide your own insight.

Part the Third: Paradise

Taking clichés to their logical extreme is one thing. Taking them seriously is another. Steinman does both at once on Bat’s most famous song, “Paradise By The Dashboard Light,” which has deliberate parallels with the title track. “Just like I wanted to write the ultimate car crash song,” he’s said, “I wanted to write the ultimate car sex song, cause those are the two important mythic icons of rock and roll. So I thought I’d take car sex to its logical extreme, where it ruins lives.”

The life being ruined in Paradise is our boy hero’s, and it gets destroyed because a girl makes him say something he shouldn’t. Remember that he couldn’t say “I love you,” in “Took the Words,” and wouldn’t say it in “Two Out of Three.” In Paradise, he goes against his principles, and tragedy ensues.

It takes seven minutes for him to succumb, which might seem fast in an actual car, but is an eternity in a rock and roll song. The tension builds progressively, as a barely seventeen temptress gets him hot and bothered, then, in another example of Steinman treating clichés as literal truths, real-life Yankees announcer Phil Rizzuto does a play-by-play about a runner rounding the bases while the couple moans and groans. Rizzuto cuts short just after the runner rounds third and tries a risky slide into home.

[dciframe]http://cdn.topspin.net/api/v3/player/195965,200,30,0,auto,border:0px solid blue;align:left;[/dciframe]

Note how he doesn’t just have to say “I love you,” which he could probably manage with all honesty in the moment. Here, the stakes are raised and he has to promise that will love her forever (he also has to make her his wife, and keep her happy till she dies). This is a lot to ask of a twelve year old.

So he resists for a full two minutes, but then,

[dciframe]http://cdn.topspin.net/api/v3/player/195968,200,30,0,auto,border:0px solid blue;align:left;[/dciframe]

And, because it’s a Steinman song, there has to be an O. Henry-like twist at the end:

[dciframe]http://cdn.topspin.net/api/v3/player/195969,200,30,0,auto,border:0px solid blue;align:left;[/dciframe]

Now, when Bruce Springsteen writes a song in which car sex ruins lives, the misery lies in what comes after the sex: the girl gets pregnant, the boy gives up whatever grand dreams he had and gets a job, and the romance of those unthinking nights down by the river slowly fades away. The tragedy is that the moments of carefree bliss are so brief.

In Steinman’s world, the misery lies in what comes before the sex, and the tragedy is that the moments of bliss don’t even exist. There are no unthinking nights, as Todd Rundgren accidentally summed up 25 years after the record was made: “I can’t imagine Steinman being in a car by the lake with the most beautiful girl in school. I can imagine him imagining it, but that’s about it.”

We’re back to the fantasy Steinman considered a key element of great rock and roll. He must have been right. The desire to experience real love and sex, the fantasies that take their place, and the desperation to act like you know the difference, describe the record, and being twelve-ish, and, I think, why it sold so well: Bat Out of Hell was Saturday Night Fever-massive, one of only 104 LPs ever to receive the RIAA’s Diamond certification for sales over 10 million.

Whether Steinman knew exactly what he was doing, or stumbled into a perfect expression of the pre-pubescent American id by virtue of his own stunted adolescence is probably beside the point. But Rundgren’s dismissive insight suggests the latter, as do some other stray facts I can’t resist sharing:

Stray fact 1: Back-up singer Ellen Foley corroborates my thesis in a documentary about the album, but her facial expression as she tries to explain Bat’s appeal is even more illuminating than her words:

[dciframe]http://cdn.topspin.net/api/v3/player/196231,400,400,0,auto,border:0px solid blue;align:left;[/dciframe]

Stray fact 2, that would probably get Ellen Foley to grimace the same way: in college, Steinman named his band The Clitoris That Thought It Was A Puppy.

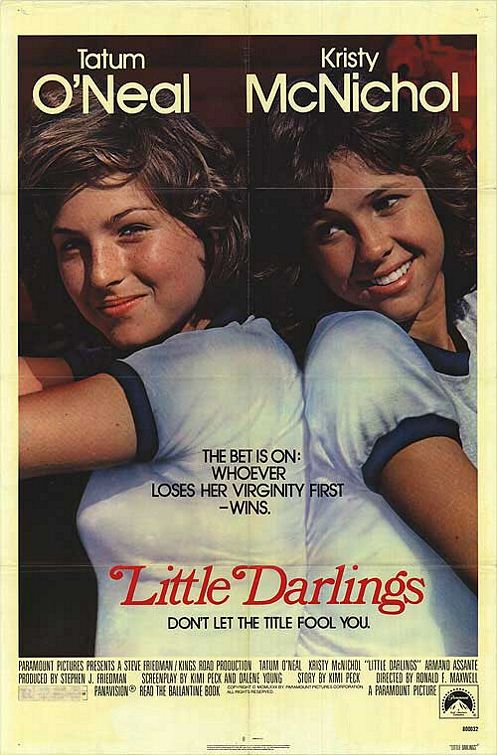

Stray fact 3: In a 1978 feature in Rolling Stone, the writer was struck by the sole adornment on Steinman’s wall: “It helps to know that his apartment…is decorated by a single snapshot of TV nymphet Kristy McNichol.”

This particular picture, by the way, couldn’t have been the one in Steinman’s apartment, as it wasn’t taken until two years later. But I’m guessing the producers of this movie saw the same thing in McNichol that Steinman did, and I’m guessing, like me, he couldn’t wait to see it when it came out.

Stray fact 4: Although Rundgren didn’t end up using it, Steinman tried performing both the boy’s and the girl’s moans in “Paradise”: “Essentially, I just made out with myself,” he says, perfectly underscoring the onanism I consider key to the album’s success.

Stray fact 5: The adjectives he used to describe his first sexual encounter to Kerrang! Magazine in 1989 seem important: “I remember shaking like a leaf the first time I was having sex. Terrified I was doing everything wrong, and a little bit horrified.”

“So what?” you might be saying. We’re all immature in our own ways, right? Indeed – our communal weirdness and clueless-ness are worth acknowledging and celebrating, and to the extent Bat does that, I still love it.

But there’s a point where pre-teen fantasies turn sour, fast, and the terror and disgust Steinman says he felt the first time he had sex also permeate the album. Granted, the album’s so deliberately cartoonish, his disgust feels more curious than dangerous – a bit like Alfalfa’s He-Man-Women-Hater’s-Club, but it’s disturbing nonetheless.

Part the Fourth: Back To Hell

Back to Farrah for a moment, since I alternated studying the LP cover with staring at her poster while listening to Bat in 1977.

That never-ending hair and those impossible teeth might be the first things you notice, but they’re not what ultimately hold the eye, at least not if you’re a straight boy of a certain age. The hook, as it were, is a little lower, and suggests she’s as excited at the thought of riding that silver black phantom bike and as impressed with the majestic death to which it leads as you are.

The thing is, the chances of Farrah getting on your bike are about as real as her smile. As good as you are at imagining, there are some places where your mind stops short.

When I was eight, for instance, I asked my older brother what I hope is a perfectly understandable question from a third grader: “I know that the man puts his penis in the woman’s vagina,” I told him as we walked to school one day. “But what if he pees when he’s in there?”

My brother replied with the sneering, incontrovertible knowledge of a ten year-old: “You idiot,” he said, “That’s what he’s supposed to do.”

Talk about terror and disgust. Four years later, I’d learned that penises could do other things, and in the process I became aware that sometimes the guys who act like they know exactly what they’re talking about are stupid liars.

But the difference between the dream of what lay beneath Farrah’s swimsuit and the reality of what that might look like was still kind of scary, at least based on that magazine I had hidden in my closet:

I’m not an anti-porn crusader. I think-slash-hope this Penthouse was, in its own way, as cartoonish and potentially harmless as Bat. But I’m convinced both speak to the same part of the brain. The first treats women as objects, while the second treats them as archetypes. And both can inspire a potentially crippling awe and fear.

Coda: All Revved Up

So, what Bat presented as noble truths now seem like sad neuroses, and what it considered demons to run from (love, sex, adulthood, genuine rather than imagined emotions) have revealed themselves to be no less mysterious than when I was a kid, but infinitely deeper and far more satisfying than I could have known.

And yet, there’s one part of Bat that still works its magic on me, even as it commits all the sins of the rest. “All Revved Up With No Place To Go” is another cliché masquerading as a title, about a lonely All American Boy who imagines he’s a wild animal circling its prey, insisting someone’s got to draw first blood, which is both a threat, and a fear, and another lame joke.

It tries to be sly and dangerous, and it fails, but in the process it distills the album’s combination of longing for and distance from sex into something that looks more and more vulnerable the longer and louder it shouts. The tricks it employs aren’t particularly novel, but neither is teenage lust.

I’m going to let Steinman, and his proxy, Meat Loaf, have the last word. The rest of the album talks the way a teenager imagines he sounds, but the last bit of this song sounds like a teenager feels: angry, frustrated, yearning, on the verge of an explosion that only gets bigger every time it fails to happen. That energy might not be worth romanticizing, but it’s definitely worth documenting, in all its goofy power.

Thanks Tim,

I was in tears as I red through your comments on bat out of hell…. I was a gay 12 year old in 1977, but all you said applies…. Espically being in love with kristy mcnickle… at the time… lol… listened to new shriekback album earlier… but today bat needs to be played.

Pingback: PvI#32: “On the Standard of [Bad] Taste” w/ Babette Babich