Here’s a longer version of the presentation I gave at this year’s Pop Conference, about Too Much Joy’s brief moment of playing protest music, and what that taught me about the skepticism that so often greets artists who take political stands. The first draft, and associated video clips, lasted 30 minutes, so I had to shave off a third of it at PopCon. This post restores the bits it killed me to lop off, although, really, I could keep talking about this for hours.

Here’s a longer version of the presentation I gave at this year’s Pop Conference, about Too Much Joy’s brief moment of playing protest music, and what that taught me about the skepticism that so often greets artists who take political stands. The first draft, and associated video clips, lasted 30 minutes, so I had to shave off a third of it at PopCon. This post restores the bits it killed me to lop off, although, really, I could keep talking about this for hours.

What I Learned in Jail

Why People Say “Shut up and sing!” and How to Make Them Stop

The most encouraging thing I have ever seen about the intersection of pop and politics was a slide in a power point deck being presented to a bunch of confused musicians at an artist activism retreat seven years ago in New Orleans.

This was the slide:

I have no idea if the statement is true, but god I hope it is. Because it means that music can not only inform listeners about political challenges, it can simultaneously convince them their participation will make a difference.

I have no idea if the statement is true, but god I hope it is. Because it means that music can not only inform listeners about political challenges, it can simultaneously convince them their participation will make a difference.

That’s a powerful notion. And I found it particularly welcome, even though I was skeptical. Because it assumes that people will willingly listen in the first place. And in my experience as both a fan and a performer, artists with a cause frequently find themselves defending their right to speak out, rather than discussing whatever issue they considered important enough to sing about in the first place.

Air Traffic Control, the group sponsoring the retreat, was well aware of this “Shut Up and Sing” phenomenon, and had been helping musicians grapple with and transcend that reality ever since the 2004 Vote for Change tour, in which musicians including Bruce Springsteen and the Dixie Chicks toured swing states advocating for John Kerry. As part of their ongoing project, ATC had commissioned a study of media responses to the Dixie Chicks’ lambasting of then-president Bush. A detailed review of over 5,000 articles and TV reports found 22 common messages, the majority of which were negative. Here are just a few:

- The Dixie Chicks are traitors and have no right to speak out against the President while on foreign soil.

- Dixie Chicks compared to liberal “Hollywood” activists and are encouraged to keep their opinions to themselves.

- Let’s play music, not politics.

- Dixie Chicks told to “shut up and perform.”

- Dixie Chicks seen to pay steep price for being outspoken against the war.

- GOP plan a South Carolina State House Resolution for Dixie Chicks apology.

- Backlash quiets music’s voices that dare to speak out against the war.

These reactions struck me as depressing, but familiar. And working with ATC (I was so inspired by that retreat I wound up joining their board) has helped me understand not just why those responses are so common, but also some strategies for dealing with them – things I wish I’d known back in 1990, when my band went through an indie rock-sized version of that same wringer.

Too Much Joy weren’t exactly a rabble-rousing gaggle of Billy Braggs, but our one concerted attempt at fighting injustice had pretty much exploded in our faces. Over twenty-five years later, I’m still not sure if this was our own fault, or society’s. It’s possible our music just activated a shittier part of the brain. Because I still believe the situation we were protesting was kind of like Trump’s presidency: such an absurd outcome the mere fact anyone even had to point out its ridiculousness felt like the battle was already lost. To me, there was zero nuance: there was a right answer and a wrong answer, and somehow, a significant percentage of my fellow citizens had proactively endorsed something that was transparently opposed to our country’s founding principles. Then, as now, I was naïve enough to assume that simply pointing out the discrepancy would somehow fix things.

Then, as now, I was woefully misguided.

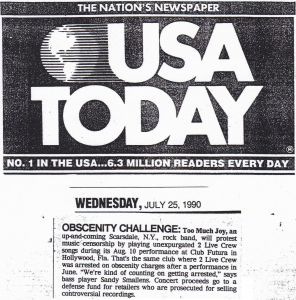

I have to detail what happened before I can explain what it taught me, so let’s rewind to 1990. Obscenity in popular music has been a political issue since 1985, resulting in voluntary self-policing by the major labels, who are still slapping Parental Advisory labels on records with curses in them today (importantly, even now a single “fuck” seems to merit one of those stickers, and necessitate a separate “edited” release for chain stores if you rap, whereas you can get away with one or two f-bombs without needing a sticker if you look and sing like Ben Folds). This initiative seems to satisfy politicians in most states, but Florida, being Florida, goes further.

Spurred mostly by a letter-writing campaign from a jerk named Jack Thompson, various county  judges issue rulings that there is probable cause to believe 2 Live Crew’s recently released LP, As Nasty as They Wanna Be, is obscene. This leads many stores to stop carrying it. In March, 2 Live Crew file suit in U.S. District Court in Ft. Lauderdale, seeking to have the obscenity complaints dismissed, but Judge Jose Gonzalez rules against them. His decision leads to the June 8th arrest of one Fort Lauderdale record store owner, Charles Freeman, and then a few days later the arrest of the group itself, after a performance of the songs at Club Futura, in Hollywood, Florida.

judges issue rulings that there is probable cause to believe 2 Live Crew’s recently released LP, As Nasty as They Wanna Be, is obscene. This leads many stores to stop carrying it. In March, 2 Live Crew file suit in U.S. District Court in Ft. Lauderdale, seeking to have the obscenity complaints dismissed, but Judge Jose Gonzalez rules against them. His decision leads to the June 8th arrest of one Fort Lauderdale record store owner, Charles Freeman, and then a few days later the arrest of the group itself, after a performance of the songs at Club Futura, in Hollywood, Florida.

My own band learns most of this from MTV News. We are in a studio in Hollywood, California, finishing up our major label debut. Several of us are stoned. All of us are outraged. While our own music is punk-pop (a term we never heard until Kurt Loder used it to describe us, later in this very story, on MTV News) we’ve been inspired enough by hip-hop to have worked up our own three-power-chord version of LL Cool J’s “That’s A Lie,” and KRS-ONE himself has just sent us a DAT with his verse for one of the songs our overpriced producer is mixing while we’re all getting angry watching cable TV in the lounge.

We work ourselves into a lather, as stoned and outraged twenty-five-year-olds are wont to do. This is all an obvious violation of the first amendment. Editorials in Billboard do nothing more than make people who already agree feel good about themselves. Someone needs to do something more substantial. The bass player suggests we go to Club Futura and do a concert of nothing but 2 Live Crew covers. This is met with hearty approval. It shouldn’t just be us, though – lots of other bands of our ilk should join us, to demonstrate solidarity with other genres. R.E.M.! Sonic Youth! 10 or more bands will appear, each of whom will do one or two of the banned songs. We have our doubts Broward County Sherriff Nick Navarro will still consider the music obscene when white groups play it, but if so, he’ll need several school busses to take us all to jail.

This is such a glorious vision that before we know it we have secured the club and booked a date in August for the performance. Stupidly, we have not yet gotten any other bands to agree to join us, although we have announced our desire for lots of other folks to participate. And over the coming weeks, we personally invite anyone whose phone numbers we have or whose managers we know if they’ll come to Florida with us. I bump into New Order’s Peter Hook in the bathroom at some Warner Records party, and implore him to join. He responds, in a Mancunian accent I won’t attempt to simulate, “No, mate, I’ve been in the nick enough as it is.”

Most other bands we speak to are less direct, but their answers are basically the same: “great idea, best of luck, sorry, we’re busy that night.” So very quickly, we are faced with a choice: do this by ourselves, or call off the concert?

We decide to move forward. The judge’s ruling is such an abomination, the fact that someone‘s protesting it strikes us as far more important than who’s doing the protesting.

In retrospect, that was wildly naïve. But even today, I find myself shocked and appalled at the way supposedly objective reporters covered the event.

This entire presentation could just be seventeen minutes of me screaming, “What country is this?!” at those reporters. The anchor starts the piece by stating “it is, in fact, a publicity stunt.” In fact! Case closed! No need to ask what we might be seeking publicity for. “Just like 2 Live Crew,” the reporter says, “this band is looking for headlines to help sell records.” There can only be one answer! The reporter said so! He’s objective!

Mind you, I have no problem with someone questioning my motives. If I had any certainty about why I do the things I do I’d never bother writing songs or listening to other peoples’ in the first place. We are all mysterious weirdoes who lie to ourselves constantly, so I expect reporters, and critics, too, to be skeptical, about everyone and everything. Please, explain me to myself. I could well be wrong!

But the horrifying thing is there’s no real skepticism here at all, there’s just a single assertion: 2 Live Crew and Too Much Joy are seeking headlines to sell records. Never mind that this is also the position the spokesperson for the sheriff’s office articulates. There’s no counterbalancing possibility, that perhaps the groups are simply seeking the ability to make records without being imprisoned. There’s just amplifying what the sheriff thinks, followed by a shrugging of shoulders that the law’s the law, and then an exasperated shaking of heads: “How long will this continue?”

There’s an easy answer to that: it will continue as long as your lunatic state keeps violating the motherfucking constitution, motherfuckers. Because that judge’s ruling was an affront to American ideals of freedom of speech whether or not my motives in protesting it are pure, and whether or not 2 Live Crew’s album was any good in the first place.

So maybe, while you’re questioning our motives, you should question the judge’s, and the sheriff’s, too. It’s a little weird that you’re accusing 2 Live Crew of seeking publicity by violating laws that were written AFTER they released their LP. Efforts to outlaw the group’s music garner headlines, and those headlines are then cited as proof the group is just trying to shock its way to fame. What other reasons they might have had for working so blue; how, when or why their music was deemed obscene; not to mention the wisdom of such an outcome, all go entirely unaddressed.

Or almost entirely unaddressed. The male anchor has a brief glimmer of self-awareness, as though he’s noticed the flaw in the report’s logic, when he points out that the sheriffs are helping us achieve our laughable aim by arresting us. If our goal were purely self-serving, the cops could thwart us by refusing to enforce the law. But that would require acknowledging the law was not really super necessary. Which was the point of our protest in the first place! Arresting someone for singing 2 Live Crew Songs would be stupid! That’s what we were saying!

They were so confident in dismissing what we were up to, they almost validated it by accident.

That clip from Miami’s channel 7 represents just one newscast, but it’s a decent proxy for the dozens  of others that ran before and after our concert, in markets large and small, on broadcast and cable networks. Newspapers and magazines from the Washington Post to Entertainment Weekly had a bit more space to dig into some of the backstory, and generally speaking they gave the notion that my band were merely cynical fame whores an appropriate amount of space – that is, they floated the possibility, without stating it as a foregone conclusion, while also making room for the idea that censorship is not something to be indulged lightly.

of others that ran before and after our concert, in markets large and small, on broadcast and cable networks. Newspapers and magazines from the Washington Post to Entertainment Weekly had a bit more space to dig into some of the backstory, and generally speaking they gave the notion that my band were merely cynical fame whores an appropriate amount of space – that is, they floated the possibility, without stating it as a foregone conclusion, while also making room for the idea that censorship is not something to be indulged lightly.

It’s possible the talking heads on TV couldn’t conceive we were after anything beyond publicity because fame in its various denominations was the only currency they themselves understood. Sheriff Nick Navarro certainly had his own complicated relationship with the concept, as he and his department were the stars of the first season of COPS, a pioneering experiment in reality TV. And the sheriff’s office seemed very attuned to public perceptions: reading the news coverage in sequence, they sound far more like politicians than civil servants bound by rules and regulations. Spokespeople initially announced we would not be arrested, then said it depended on what deputies saw when we performed, before finally settling on this Navarro quote: “I arrest anyone in Broward County who breaks the law,” a sentiment that would be a lot more convincing if nobody who worked for him had previously contradicted it.

After the show was announced, I spent a few days transcribing the lyrics to the songs on As Nasty As They Wanna Be, which entailed hitting the pause button on my CD player a thousand times, and double-checking the bits I could only guess at with people better versed in their ouvre than I. While I was happy to defend Luther Campell’s right to create boundary-challenging art, I was less enthused about the boundaries he chose to ignore, or the clumsy way he went about it. His beats felt mundane, his samples uninspired, and his punchlines cheap. The bulk of the lyrics struck me as juvenile and transparently misogynistic. You didn’t need to be a hip-hop expert to recognize just how disappointingly low 2 Live Crew were aiming compared to so many of their peers.

My opinion of 2 Live Crew’s art was and is completely beside the point, though. The freedom for citizens to say controversial, stupid or offensive things is a pre-requisite to debates about the worth of what they’ve said. And I will say that working up our own punky takes on the six songs from Nasty that seemed like they had the best chance of making some kind of sense in between our own material (after attempting several, we settled on “Me So Horny,” “Dick Almighty,” “Dirty Nursery Rhymes,” “The Fuck Shop,” “Get the Fuck Out of My House,” and “If You Believe In Having Sex“) gave me an appreciation for what they were up to that went well beyond the words. The way “Fuck Shop” used the riff from “Little Bit O’ Soul” to give the B-verses a lift, and the irresistible way the call-and-response chants in “If You Believe in Having Sex” encouraged rather than demanded audience participation both spoke to a band that had other weapons besides shock value to override an audience’s super-ego, and communicate directly with its id. Typing, “All the ladies say, ‘Eat this pussy, eat eat this pussy,'” was awkward. Shouting it in a club over a simple but infectious beat, and watching how enthusiastically everyone – not just the ladies – said exactly that, was exhilarating.

Which doesn’t make it right, or good. It just gives me a few more reasons to be suspicious of anyone who’s so afraid of that phenomenon they’d prefer to make experiencing it against the law, rather than persuade me I should investigate my reaction after the fact.

Two nights before the concert, we made our network TV debut, on CBS’ late-night talk show. We performed our cover of “That’s a Lie,” insisted we were heading to Florida to protest censorship when the host congratulated us on our “good publicity stunt,” and noted that the sheriff’s latest position was that he would not be arresting us. To his credit, the host acknowledged, “That would be sort of racist.”

I confess I was a bit terrified from the moment we landed in Florida. I was confident in the righteousness of our cause, and I knew we had some pro-bono ACLU attorneys ready to spring us from jail if/when we wound up there. But I was also painfully aware that we were interlopers with suspect motives, and the sheriffs and deputies and judges and juries had all kinds of ways of exhibiting their displeasure if they didn’t see this issue quite the same way as I.

The show itself was over pretty fast. Charles Freeman, the record store owner who’d already been to jail over this insanity, emceed. We did the six 2 Live Crew Songs we’d worked up, four of our own, and ended with “I Fought the Law.” Since our cover of “That’s a Lie” included a false stop, during which I habitually dropped in a site-specific lie each night, I vented my frustrations with the way newscasters had been framing the event by saying, “We all know this is just a publicity stunt,” before my bandmates kicked back in with the title phrase.

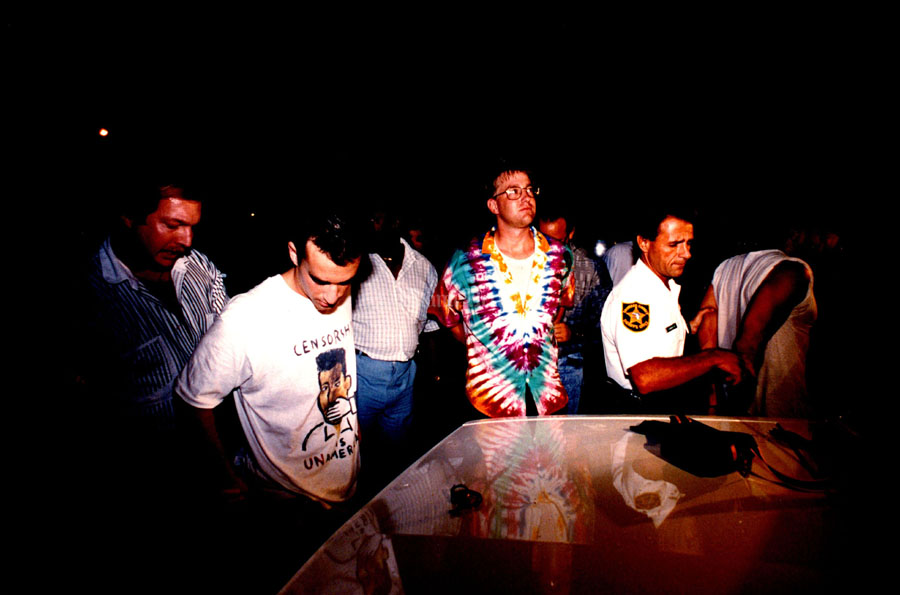

And then we went to jail.

I’ll grant that the bass player’s careful substitution of “baloney” where he was about to say “bullshit” indicates a person who’s aware he’s on TV, even as he’s being handcuffed, and is making sure his point can still get aired. But note the point he’s making: censorship is bullshit. Then note the weasel words the anchor uses right afterward: “many people think,” which disguise opinion as objective reporting of fact. I wish I could believe she thought Sandy had made such a compelling case that professionalism obligated her to present the counterpoint.

But she’s not injecting necessary nuance into what we’ve mistakenly presented as a black and white issue, she’s substituting her own, irrelevant black and white conflict, then leaving us to defend ourselves against that. The fact that two different groups have now gone to jail isn’t taken as an indication the law might be crazy, but only as a evidence that some other mercenary jerks want in on this sweet, sweet, PR gravy train.

The whole evening’s debacle was so absurd that, even twenty-seven years later, it’s difficult for me to separate the farce from the horror, or to articulate how desperately I clung to the former to prevent being overwhelmed by the latter. The farcical elements are easy enough to enumerate. The deputies came undercover, but as they were apparently unaccustomed to attending rock shows, their disguises consisted of Hawaiian shirts, fingerless gloves, and bulky camcorders to document our crimes. Our drummer, whose day job was being a New York City cop, escaped through a back door while our guitars were still echoing feedback at the end of “I Fought the Law,” since an arrest would have gotten him fired. As the bass player, guitarist and I were being shoved into squad cars, one overzealous deputy said, “There were four of them, where’s the other?” A more seasoned officer replied, “Only these three sang.” The deputy insisted, “But I saw the drummer mouthing the words.”

Maybe that last one should go in the horror column. Like I said, the combination of the merely ridiculous and the truly frightening was super weird. An agent of the state wanted to incarcerate a musician for lip-synching curses. Is that funny or terrible? The sheriff who handcuffed the guitar player whispered, “I like your shirt,” (which said “Censorship is Unamerican”). Was that a welcome sign of solidarity, or one more example of the banality of evil? Some of the cops sang 2 Live Crew songs while booking us, and every single one cursed up a storm, often utilizing words I personally found more problematic than anything we’d said onstage. Is that genuinely fucked up, or were we all just playing our assigned roles in a goofy pantomime?

The one thing that will always and forever go in my horror column is the sound (and the feeling) of the door slamming shut behind us in jail. I knew we’d be bailed out within 12 hours, and given all the news cameras waiting outside I was reasonably sure we’d emerge bruise-less. But that couldn’t erase the simple fact that we’d been thrown in jail for singing songs. Granted, I am a terrible, pitch-challenged singer, encouraged in all the wrong ways by Jonathan Richman and Lou Reed that actual vocal ability is beside the point. And we had all been so nervous, and the crowd had been there more for the spectacle than for our set, that we’d sucked even more than usual. But still: in America, you are not supposed to be arrested for making shitty art.

Also, in their one blatant fuck you to the uppity Jews (and bandmate of Jews) who’d come to their state to tell them what to do, the cops charged us with felonies, rather than misdemeanors. The charges would be downgraded before we went to trial, but in the moment it meant the door that slammed behind us closed us in a room with a bunch of folks who had allegedly done even more terrible things than curse on stage, and who had definitely been in this room more often than we.

Any fear this was meant to engender only lasted a moment, though. While my understanding had always been that if you wind up in jail, you’re not supposed to ask anyone else what he’s in for, or volunteer what got you arrested, we’d been on the evening news, and it turned out most people there had been arrested after seeing the reports about our concert. They, at least, were all very supportive. So I can cite at least one PR benefit that accrued to my band: our fellow inmates were nice to us because we’d been on TV, talking shit about the Sheriff.

Post arrest, pre-trial, we made the rounds of radio and TV talk shows, still stubbornly assuming they’d provide an opportunity to argue against censorship. The difference between our ideals and the fallen world we actually inhabit were never more pronounced than the morning I roused myself earlier than usual, quite hungover, and called into a radio show in DC that had requested an interview. Remember, this was 1990. Rush Limbaugh had only been broadcasting nationally for two years, and was still building his audience. Fox News’ birth was still six years in the future. I had zero experience of unhinged conservatives screaming about how me and my ilk were destroying our country. I had no idea such shows existed. Until I got patched in.

Needless to say, we never got as far as debating censorship. Before I knew it, the host was asking me if I did drugs. I had, in fact, done drugs the night before, and still had enough lingering paranoia that the fact I had dialed into DC suddenly seemed important, as that’s where the FBI were based. I stammered, “Not anymore,” convincing myself it was true in the moment because I never would again.

That one was an outlier only in how little lip service the host bothered giving the ostensible subject of our interview. But it didn’t really matter how respectable the venue – from the McLaughlin Report to Phil Donahue, my bandmates and I found ourselves shouted down by hosts and panelists not because they thought censorship was a good thing, but because they understood something we didn’t: conversations were not the goal of these entertainments. Conflict was.

Eventually we learned the value of pivoting off a host’s premises rather than meekly denying them.

We weren’t any better at pretend debates on network TV than we were at playing 2 Live Crew songs, but we’d learned just enough of both to fake it for a half hour. Both were games, in a way: make your point as simply and repeatedly as you can. I’m a little pissed at my younger self for giving the “it’s just PR” critique any hint of legitimacy, but it was almost worth it just to see smarm-meister Bill Maher get shut down by those kids.

Charles Freeman had his trial in December; he was convicted of selling obscene material to minors and fined $1,000. 2 Live Crew’s trial on their obscenity charges took place two weeks later. They were acquitted.

So the DA was batting .500 when our own trial began in January of ’91. And that’s when I learned there were important legal ramifications to insisting our concert was just a publicity stunt. Since the Supreme Court has defined obscenity as, “material that appeals to prurient interest, depicts, or describes sexual conduct in a way that is patently offensive, and lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value,” our prosecutors had a big challenge. Not only did they have to argue that our performance appealed to the prurient interest and lacked any literary or artistic value, they also had to convince the jury it wasn’t a political protest. This seemed difficult, to me, given that I had introduced the set by saying, “Welcome to our political protest.”

The Assistant District Attorney tried his best, stating that, “Despite the singer’s self-serving assertion that this was a political protest, it was not.” Happily, this was not a winning argument: the trial took three days, but the jury returned a Not Guilty verdict after deliberating for just 15 minutes (they said it would have been even faster, but some of them had to use the restroom). Ken Gerringer’s charges, which were scheduled to be tried the following week, were dropped. The DA announced he would no longer prosecute obscenity claims related to the 2 Live Crew album.

So, mission accomplished, in a very concrete way. If we were after publicity, however, we chose poorly. The courtroom had been packed with reporters the day our trial began. But halfway through day 2, Operation Desert Shield morphed into Operation Desert Storm, and the U.S. began its “shock and awe” bombing campaign in Iraq. The courtroom was nearly empty for the remainder of the trial, and the actual verdict barely registered on the national radar. One of our pro-bono attorneys confessed he was a bit disappointed, as he’d assumed he’d emerge from the case with more attention. I didn’t really mind at all. I just wanted to go back to playing our own music.

Which we did. “Fuck Shop” remained in our live arsenal whenever we earned a second encore, but beyond that I pretty much forgot about the incident, and didn’t give much thought to what we could have done better until that slide I projected earlier made me wonder where we’d gone so wrong. My work with ATC (recently re-named RPM, for Revolutions Per Minute) has actually done a lot to wash away the bad taste talking to people like Bill Maher left in my mouth. I remain inspired, for example, by Chicago punks Rise Against, who got bored with the standard tour imperative to do meet and greets with radio contest winners, and started taking them to local food banks, instead, where everyone involved wound up having a much better time than they might have otherwise. Watching other musicians navigate these waters is always instructive, even when they capsize.

The only way to avoid capsizing I’ve found is the Fugazi approach, which entails maximum political engagement, but solely on your own terms. As Ian MacKaye sums it up: “The mission was never to destroy the state, it was to create our own state.” So he and his band focus on what he calls “the nuts and bolts.” They raise money by playing benefits, they donate their own money to the causes they care about, and, arguably most importantly, they model a world in which the band provides more than mere entertainment. But they rarely do TV interviews. “I have always turned down major media stuff, especially television,” MacKaye says. “Those talk shows, once you’re in there, they hold all the cards. It’s very hard, I think, to have a really legitimate conversation in that kind of setting. All they are is advertising vehicles, so if you go on there you must want to advertise. I think it’s very difficult to game that.”

Because they refuse to play on anyone else’s field, they almost never have to respond to hostile framings of what they’re up to. MacKaye uses an analogy of two 50 gallon barrels to explain this, one stainless steel, perfectly clean, and empty; the other filled to the brim with excrement. As he sees it, “You could take a spoonful of shit and throw it into that clean barrel, and you can spot it. But you can’t throw a spoonful of clean into that barrel full of shit. It just becomes shit. And that’s always been my kind of principle in general, you can’t be anything but what it is, once you enter that machine.”

Ironically, if Fugazi did start doing TV interviews, they probably wouldn’t face the backlash the Dixie Chicks did, as Jenny Toomey, who was Executive Director of ATC during the Vote for Change tour, explains: “The whole ‘shut up and sing’ thing happens a lot to people who haven’t in any way embodied any political voice in any of their work. The Dixie Chicks dropped in on that issue…the way they portrayed themselves didn’t naturally extend to ‘we hate our president.’ Think of it as an Evel Knievel jump over a too far canyon, and they fell. If they’d sort of built a bridge across the canyon, people would understand how you could get across.”

Toomey watched Bruce Springsteen become someone who gave a better stump speech for Kerry than Kerry himself. But she emphasizes that it didn’t happen overnight. “He was so much clearer. He was so much more grounded in values than politics and political theory. He was so much better a communicator than Kerry ever was. But what was fascinating to me about all of this is even a Bruce Springsteen, someone who’s a really thoughtful, values-laden, interesting, charismatic communicator, isn’t going to become a great political stump person overnight. You actually need to practice.

“And it’s so funny because you’d never think, ‘OK, Kerry, I’d like you to come and do a guitar solo to open for Bruce.’ You’d just laugh, because it’s ridiculous. Politics is at least as complicated, and finding your political voice is as hard or harder than writing a great song. So I think the thing that artists do that hurts themselves politically is to not put the time in.”

OKGo’s Damian Kulash, another ATC retreat alumni, notes that, unlike politicians, most musicians aren’t accustomed to having 50% of the audience boo them no matter what they say. “We generally are used to dealing with self-selecting groups of people who like us. So I don’t think the problem is so much that musicians face too much resistance, but that we’re unaccustomed to much resistance at all, and we forget, when we dip our toes into politics, that resistance is the norm, there.”

My band should have expected more resistance. Then again, the very reason I was so flummoxed by accusations of cynicism is that we never had any grand strategy. All we had were sincere convictions that something terrible was happening, and a strong desire for it to stop. So the notion that we were mercenary masterminds was bizarre, given that we could barely string our guitars.

In a weird way, those talking heads on TV were granting us more credit than we deserved. But I still think they were unwitting forces for evil. And as appealing as I find the Fugazi approach, I’m pretty sure there’s value in fighting such forces on their own turf, even if you get shit all over you in the process. It might not be possible to throw clean on the judges, or the sheriffs, or TV hosts.

But it’s almost always worth trying.

All I thought I knew about this incident prior to today was that TMJ got arrested once for performing 2 Live Crew songs to protest obscenity laws. I don’t think I ever made the assumption that it was a calculated “publicity stunt” but I am pretty sure I grossly mischaracterized the event in my head as a “youthful prank”, over and forgotten the next morning. I wasn’t even aware that there was an actual trial. I am so glad you took the time to describe this incident in depth – your motivations, what really went down all those years ago, and what you took away from the experience. Particularly interesting is the assumption by many that it was a “publicity stunt” and the less than positive interactions with the media that ensued “because they understood something we didn’t: conversations were not the goal of these entertainments. Conflict was.” By the end of the media attention on the matter did you feel you had sufficiently honed your approach to interviews about it? Thank you guys for doing what you did!

We got better as time went on, without ever getting great at it.